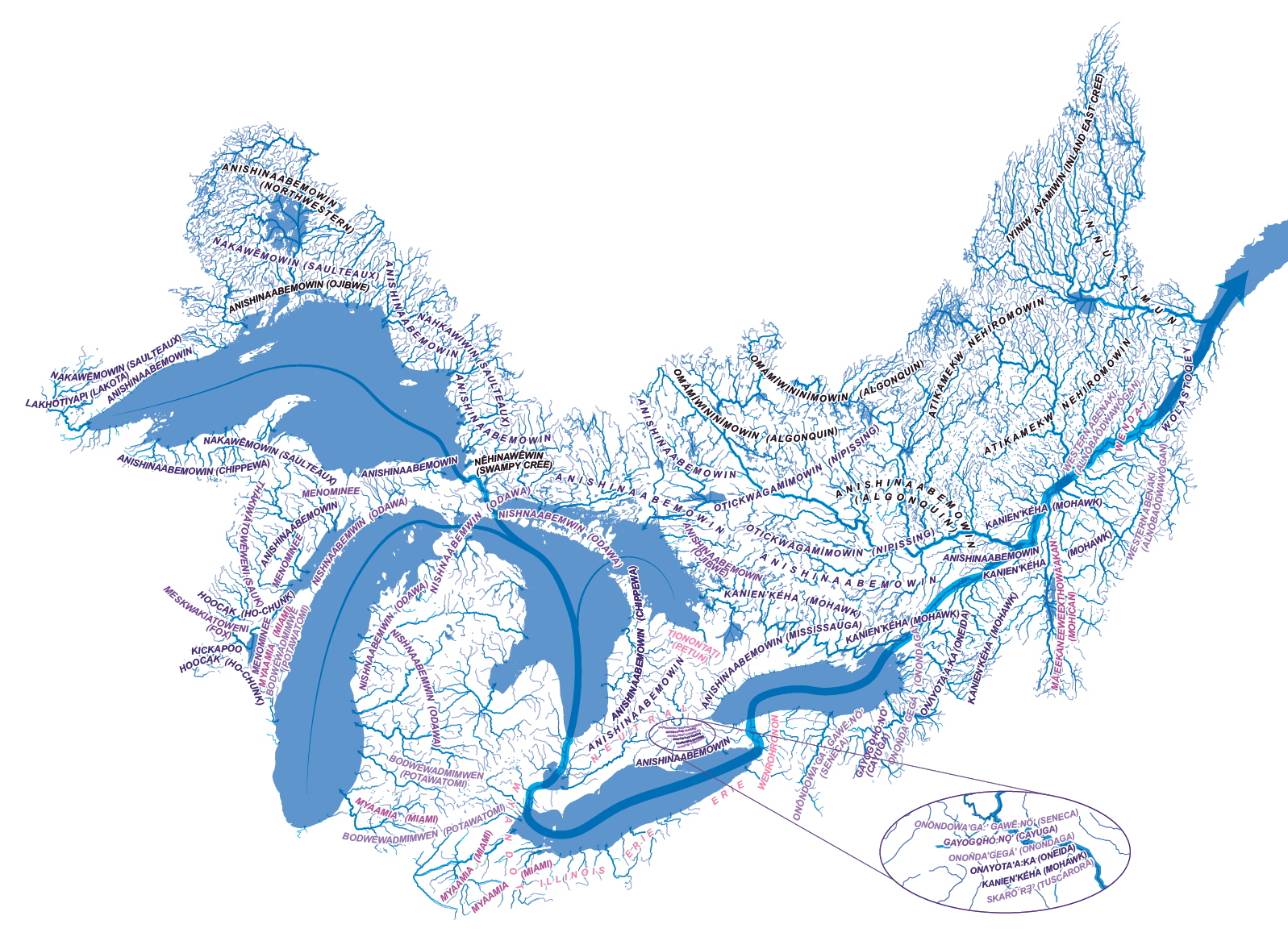

Original languages of Great Lakes.- St. Lawrence watershed. Map by Chris Brackley.

In honour of all the Indigenous languages born in — and irrevocably tied to — the land surrounding the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence watershed, Biinaagami is launching a five-part series on Indigenous languages. Today’s introduction also coincides with Canada’s National Day for Indigenous Languages in which the nation promotes the use of the Indigenous languages, decades after systematically destroying them through the Residential School system and assimilative policies.

This series is meant to bring awareness not only to the threats that our languages face but also to the dedicated individuals pouring all their love into reviving them — often at great personal cost. According to UNESCO, there is not a single Indigenous language in the watershed that is considered “safe.”

While each Indigenous People has their own culture, artworks, stories and languages, we are united in the way we are intertwined with the land and her waters. There are more than 200 First Nations within the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed, all of whom are bound to the waters through our shared responsibility to love and protect Mother Earth.

To illustrate some of the Original Peoples’ ways of thinking about water, Biinaagami, an Anishinaabe name meaning “pure, clean water,” sought out four language keepers to share how their language binds them to this watershed. In conversation, we gathered water-related words from each speaker, offering insight into their cultures, and gifting our readers some words to carry with them too.

As you read these interviews over the coming month, we invite you to reflect on how these terms offer perspectives about water and how terms in your own language may do the same.

In these four conversations with language keepers, young and old, we found that Original Peoples’ terms and ways of thinking about water are ultimately conduits to strengthening relationships between people, waters and land, regardless of Nation. These connections help us orient ourselves within the natural world, rather than above it. Teachings and values about water are inherently carried in these languages.

So, losing languages and dialects is not just about losing words; it’s losing connection. It’s losing connection to the waters, to the land, to our ancestors, our oral histories, songs, ceremonies, dreams, and all the non-human beings in the natural world that work together to help sustain life — our lives. The languages that carry such teachings need our help to be spoken back to life.

One of my Kanyen’kéha teachers says to use and teach whatever words we can, whenever we can. Do it even if we stumble over the pronunciation or become angry with our lack of fluency in our own native language – or angry that our fluency was stolen. In that way, we each carry a little piece of the puzzle that keeps these sacred connections alive. So, I invite you to start with a few words from my language. Speak them badly if you have to.

Wa’tkwanonhwerá:ton tsi wésewawe Biinaagami. Konoronhkwa. “Welcome to Biinaagami. I love you/ you are precious to me”.

Wa’tkwanonhwerá:ton: [what-gwa-noo-hweh-rah-doo]

Tsi: [Jee]

Wésewawe: [weh-say-wah-way]

Konoronhkwa: [Guh-no-roong-kwah]