Portrait of Karonhianonha Francis by Miskwaa Designs.

My name is Karonhianonha Mikayla Francis. Karonhianonha translates to “She Protects the Skies” and I’m Wolf Clan of Akwesasne Territory. Akwesasne is within the Mohawk nation that is within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Today, we’re talking about the water and I think that’s really unique to Akwesasne considering all four major waterways from the Adirondacks meet at the international seaway at Akwesasne. That also pertains to the breakup of jurisdictions and governments that we have here.

The water is definitely a big factor in the way Akwesasne is the way it is.

I’ve done a little bit of research in the past on the traditional names of the land, and it really tells a story of the geographical location. For example, I grew up in Frogtown but in Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) it’s Ohtskwahe’ne – “where the Frog lives.” There’s also Ahnawá:te which is Raquette Point, but it is referring to the rapids. Kawehnò:ke is Cornwall Island, but it means “the land is surrounded by water.”

There’s a lot of islands within Akwesasne’s territory. As the seaway goes up into Lake St. Francis, all of those rapids have pulled a lot of stories — the way the river has carved out and hidden islands and re-submerged islands throughout history.

Looking back at Akwesasne’s timeline, waterways were our original roadways for travellers. That comes out in the language — it leaves hints here and there. The waterway could be the Mohawk word on the roadway signs throughout Akwesasne. You really start to understand the location — the story — when you understand the language. Our language is very descriptive. The water relates to the land. This comes from relation — and it’s how we, as users of Mother Earth’s waters, see.

On how the waters have changed

From my childhood to adulthood, the waters have changed — I’ve seen it, even throughout my short life so far. Drastic changes came with the removal of a dam, bringing back a lot of species that were almost extinct in our area.

You grow up playing on the river on canoes, kayaks, on the boats fishing. Those kinds of things you really look forward to in the summertime — especially not having school! At a young age, you kind of grow that appreciation all year round. ‘I can’t wait for it to freeze so I can skate, can’t wait for it to melt so we can swim.’ But there’s this change that I’ve noticed in my experiences of water, so I’ve been reflecting on how I was connected to it.

There’s been a lot of high mercury and PCB-3 [polychlorinated biphenyls; a human-made chemical] levels, which should come with a huge flash warning. It’s a neurotoxin that can cause brain cancer. Our fish are carrying these high levels of PCBs in our waters because of these drastic changes that the next generation is really paying attention to.

I’m paying attention, too, and have joined a local group called Healthy Rivers Nothing Less. We’re just a handful of concerned community members raising awareness and concern for the water for our next seven generations. The concern is high and real in modern-day Akwesasne — that our water could be at risk in the near future. I think we’re seeing how a lot of things in our area have been taken for granted, from fishing to eating healthy fish to making pottery.

I know there was a lot of clay but then because of that mercury in the clay, firing it up is just not good. Our fine arts used to thrive here, and I think basket-making could be the next one to go. Where we see our waterbeds, where the sweetgrass grows, we know those things are all very much connected: our environment, our land and water, and everything that is in between… these things are of concern right now. It’s all related.

On song, and the connections to water

When I think about ohnekanos, water, the first thing I think of is the Water Song. As a singer, that’s what I always fall back on because water was my first relation … The water song was one of the first songs that was embedded in me at a really young age. It was more than music; it was intentional, ancestral — and it was that strong connection to something that is supposed to be embedded in everybody. That was the first time realizing intentional, ancestral music was with a purpose. A lot of power comes with that, and so that Water Song was just like reflecting on how water connects us.

On the memory of water

Researchers learned that the [ancient] pottery pots [that were submerged on an island in the St. Lawrence River around Akwesasne then re-emerged] were created by left-handed people, and that’s due to the way that they’re designed and how intricate the details are. They can tell that these pottery shards are made by left-handed people. I always think that’s so crazy because I’m left-handed. I find out these cool facts that just make me feel a little bit more connected.

That’s also really important when I share some of the truth and realities that come to the way left-handeds weren’t appreciated in Residential School times and some of the ways that pains were inflicted to force change against what we’re just naturally born with. As we look throughout history and the beautiful side, there are things that we can still reclaim and come back to. The water has all of these histories and we can notice her changes as they affect us as well.

On water and the cycles of the Earth — and us

The water is alive and has a life force. We are all made up of water. When we talk about the next generations and the connectedness between water, land and people, scientifically and spiritually, Grandmother Moon is another life force.

The first thing that you have to explain is the entire Creation Story, and of course we don’t have three days! The sped-up version is: this world was water before land was created — and we call this land Turtle Island because that was the original being who assisted Sky Woman (who would later become Grandmother Moon) in creating a sustainable ground for her to bear her child. And so when our oral traditions tell us these things from the very beginning, we understand a certain perspective and appreciation.

The symbolisms that we take from the Creation Story are all rooted within the scientific explanations of today. The paces and the spaces on the turtle’s back is 13 — that represents the 13-moon cycle. And then the 28 around the outer edge is the 28-day cycle within each moon phase. Our calendars have added some days and taken some away each month to make it even out, but the natural moon phases are embedded in our creation story.

That 28-day cycle of renewal and coming to a full moon moves the water — and creates those tides here, physically, on Turtle Island, but also within each person, scientifically and energetically. Because we all carry that water, and women carry the water of life, those are things that can affect us. Those are some of the reminders that I want to engage the next generation in, but it’s also a reminder to appreciate good clean drinking water, even at a young age.

Those water connections that we feel throughout the month correlate to women’s moon cycles (menstruation). And so that can tell you the phase of the moon will match up with the phase of your body at its natural time.

That’s exactly why we have the Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen (Thanksgiving Address) to begin all things and end all things — to bring all minds together and remind us all at the same time that all of these natural elements would thrive without human beings, but human beings would not exist without even one of these natural elements. They’re still doing their duties, and we have to thank them for that. When we break down what all these different beings do for us, the small issues just seem to fade away. I think that’s a different mentality that Kanien’kehá:ka grow up with naturally. It’s important for the language to be embedded into these traditional teachings that are in their revival period for our next several generations.

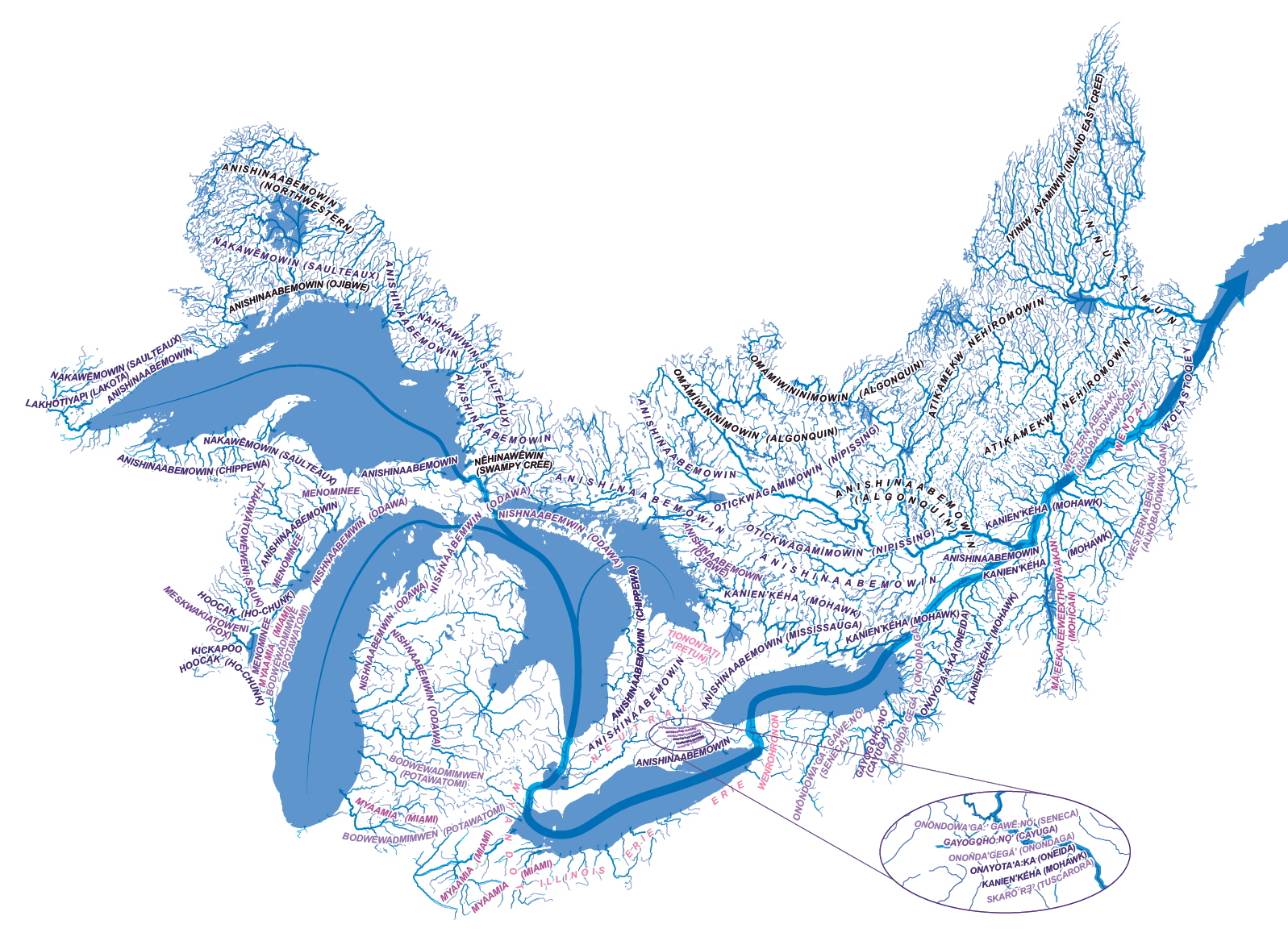

Original languages of Great Lakes.- St. Lawrence watershed. Map by Chris Brackley.