Dr. Susan Chiblow. Photo from the International Joint Commission.

The Canadian Cabinet has recently appointed Dr. Susan Bell Chiblow as one of three Canadian commissioners for the International Joint Commission. The International Joint Commission is a non-partisan consulting body for both the Canadian and United States government for investigating transboundary water issues, recommending solutions and approving actions while taking into account the needs of a wide range of water uses.

Dr. Chiblow is Anishinaabekwe from Garden River First Nation, Ontario, where she continues to reside. With over 30 years of experience working with First Nation communities in environmental related fields, and extensive academic accomplishments including a Ph.D focused on N’bi Kendaaswin (Water Knowledge), Dr. Chiblow brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to her new role. Additionally, Dr. Chiblow has worked with the Chiefs of Ontario as the Environmental Coordinator of the Environment Unit, and continues to work with First Nation communities and Elders on environmental projects.

Her appointment succeeds Mr. Henry Lickers, the first Indigenous Commissioner at the International Joint Commission, who served from 2019 to 2023.

The Biinaagami team applauds this appointment, and we wish Dr. Chiblow all the best in her new role.

Construction of radioactive waste “near-surface disposal facility” approved

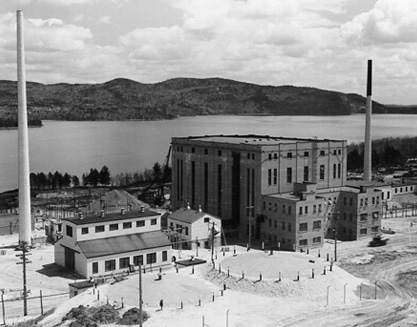

NRX and Zeep buildings, Chalk River Laboratories, 1945. Photo from the National Research Council Canada Atomic Energy Project.

On January 8, 2024, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission approved the construction of a “near-surface disposal facility” to dispose of low-level radioactive waste on unceded Algonquin territory in Chalk River, Ont. Approval was given despite strong opposition from Algonquin leaders and other First Nations since 2016 when the review process began.

According to Chief Dylan Whiteduck of Kitigan Zibi, one of the Algonquin chiefs who opposed the new construction, “the Chalk River nuclear site was created without free, prior and informed consent. We have never agreed to this, and it continues to be operated on our unceded territory.” Free, prior and informed consent is one of the rights outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was given Royal Assent in Canada in 2021.

Algonquin leaders have opposed the site over concerns about the ecological impact and the risk of water contamination — an ongoing issue in First Nations communities across Turtle Island. Though, the Safety Commission cited that the new facility is “not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effect.” The next step in it’s construction will be for Chalk River Laboratories to apply for a separate license to operate the facility.

Chalk River Laboratories was originally built in 1945. It would become the site of the world’s first nuclear reactor partial meltdown in 1952, leading to drastic changes to reactor safety and design, followed by a second incident in 1958. This is a legacy not soon forgotten by the Algonquin Peoples who depend on clean waters and healthy lands in the area. They’re not alone in their disappointment.

Theresa McClenaghan, executive director of the Canadian Environmental Law Association, worries, “the design of this facility is tantamount to an ordinary domestic landfill and we know that such facilities always eventually leak to the surrounding environment.”

Winter seiche reveals historical artefacts beneath Lake Erie

On January 12, a wind storm that brought gusts over 95 kilometres per hour was forceful enough to displace the lake toward the east, revealing the lake bottom around the Toledo, Ohio region. Locals of the area were able to explore the exposed coastlines and islands of the western part of the lake.

Photos said to be taken near the James A. Haley Boardwalk in Oregon, Ohio, depicted what looked like an uncovered shipwreck.

National Museum of the Great Lakes Director of Archaeology and Research Carrie Sowden said that the images of the exposed structure were not enough to confirm whether or not it was the remains of a long-lost ship. “From the photos I looked at last night,” says Sowden, “I saw a lot of straight lines, which to me says more pier/dockage than ship – that’s just my first impression.”

Other objects, such as what appeared to be an old cannon, were also likely something else, obscured by watery weathering over time, Sowden suggests.

Lake Erie is the shallowest of the Great Lakes and contains numerous shipwrecks. “Even if it’s just a pier,” says Sowden, “it appears to be a lost, unknown remnant of something people in this area don’t necessarily remember.”

Sowden had hoped to investigate the structure, but the window of opportunity closed when the Lake Erie water table quickly levelled out.

The historical remnants beneath the harbour will have to lie in wait until another wind storm comes along with the capacity to expose them once again.

Watershed Wednesdays are our weekly roundup of the insightful, intriguing, important and inspiring news from around the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed.