Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore — one of the five parks that is part of the decarbonization plan. Photo by Charlie Wollborg.

In an effort to combat fossil fuel emissions and reduce the amount of carbon polluting Lake Superior’s natural and cultural resources, the National Parks of Lake Superior Foundation is formulating an “ambitious” project to pursue net-zero energy consumption through park facilities.

“What makes our plan so unique is that we’re the first parks group to have a really comprehensive strategy and game plan with actual data on how to do this throughout each park,” says Tom Irvine, executive director of the NPLSF.

Askov Finlayson, a climate-positive outdoor clothing company, approached NPLSF in 2022 as a private donor to fund and support a project that would benefit Lake Superior parks for years to come. With their guiding hand, the Decarbonization Plan was developed.

“One of the things they were most interested in is just really climate and sustainable energy and how those things could be married into a program that would benefit the lake and the parks,” says Irvine.

The Decarbonization Plan is a comprehensive strategy to address the individual needs of each park with a combination of technological energy-efficient upgrades and zero-carbon energy sources. The plan covers five parks: Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Grand Portage National Monument, Isle Royale National Park, Keweenaw National Historical Park, and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore.

The plan involves implementing the use of solar technology and PV battery storage for the parks that do not have grid access and replacing propane and natural gas with clean energy air and heat pumps. While the larger components of the project involving major construction and building have been slow-going, the NPLSF is working to replace fuel-operated vehicles and equipment with electrical ones.

“At Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, we’ve transitioned the trail maintenance crew to battery-powered chainsaws and trail maintenance equipment,” says Irvine. “When these trail crews go back to clean trails and do the work, they’re not hauling gasoline into the wilderness. They’re not polluting the air with the loud sound of chainsaws and blowers and equipment, and really providing a safer environment for the trail crews to work with.”

Seeing as the parks’ carbon footprint is relatively small, one of the main objectives for this project is to be an example for the public, to prove that decarbonization is possible and can be achieved.

A new hydrogen facility sparks concern within Akwesasne

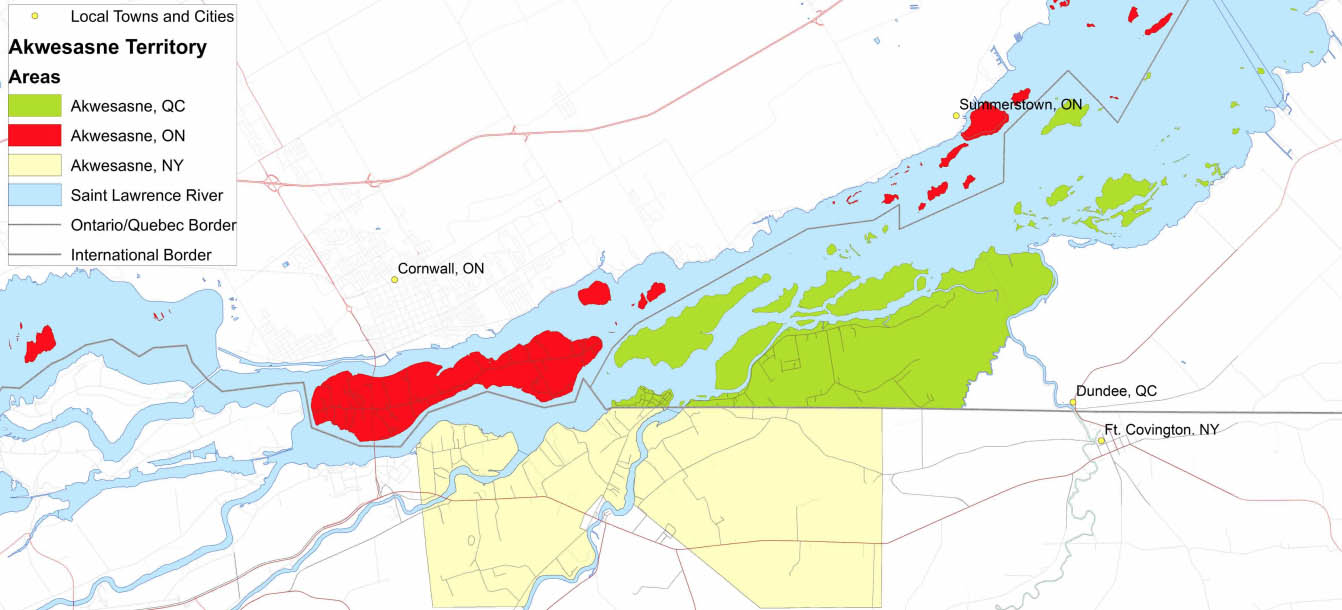

Map by Akwesasne.Travel.

Tensions arose between the Akwesasne Mohawk community and industrial gas company Air Products and Chemicals Inc. following the proposed development of the New York Green Hydrogen Facility.

In March, Air Products announced their plans to build a facility to produce green liquid hydrogen at a greenfield site in Massena, N.Y., approximately 30 kilometres west of Akwesasne. Akwesasne straddles the Ontario, Quebec and New York borders, splitting the Kanien’kehà:ka (Mohawk) community between Canada and the U.S.

Prior to the announcement, Air Products had been communicating with the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, the branch of government responsible for the American side of Akwesasne. However, the company neglected to consult the Mohawk Council on the Canadian side, causing a stir within the community.

“It totally doesn’t go with free, prior and informed consent,” Dr. Ojistoh Horn, a physician with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne’s Department of Health, told CBC News.

The facility will produce 35 tonnes of carbon-free liquid hydrogen per day, using water from the St. Lawrence River. Further concerns surround the possible environmental and health effects caused by water discharge proposed to flow to the Massena Power Canal, which connects to the Grasse River and eventually to the St. Lawrence. If any contaminants make it out into the river, it will flow downstream into Akwesasne territory.

An 80-kilometre stretch of the river where both Massena and Akwesasne sit is a historically hazardous and contaminated area and remains a designated “area of concern” by Akwesasne, the U.S. and Canada. The prospect of further pollution, such as polychlorinated biphenyls, is daunting to Akwesasne residents.

“I’m very concerned that the effluent discharge from Air Products is going to disrupt the PCBs that have been so-called sequestrated,” Horn told CBC.

Air Products hosted a public information meeting with residents at the Akwesasne Mohawk Casino on March 11 to address concerns and to provide details concerning the timeline of construction and the environmental process. While concerns regarding the lack of communication with the Canadian side of Akwesasne and environmental impacts still stuck with residents at the end of the meeting, it was agreed that open communication would be maintained between Air Products and both sides of the Akwesasne community.

Lower-than-usual water levels amount to higher-than-usual dead fish along the St. Lawrence River

A skyview of the St. Lawrence River flowing by Montreal. Photo by Shayan Ghiasvand.

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is investigating after a troubling number of dead fish were found along Montreal’s South Shore earlier this month.

A percentage of fish die-offs are expected each spring; however, this year’s numbers were unusually high.

The St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation (SLSMC) controls the water levels in certain channels and canals to facilitate maintenance procedures ahead of the navigation season.

Philippe Blais, biologist and founder of Vigile Verte, thinks it probable the routine procedure might be behind the large number of dead fish. “Anything that isn’t adapted to move too fast, everything that lives on the bottom, well they’re not adapted to being without water, especially in freezing temperatures,” says Blais.

Low water levels can trap aquatic animals and organisms in shallow puddles that eventually dry up, eventually causing them to die of asphyxiation.

Blais says the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation dropped the water levels lower than normal this year. “We’d like to know exactly what the reason is for doing so,” he said.

SLSMC external relations vice president Jean Aubry-Morin suggested “reduced ice cover, water evaporation from the basin related to warmer weather conditions combined with other factors related to climate change would all have contributed to the observed situation.”

“The DFO will be in contact with the SLSMC for further information,” says Fisheries and Oceans Canada spokesperson Tomie White. Vigile Verte say they hope the DFO conducts a meaningful investigation into the issue in order to prevent the situation from happening in the future.

A strong start for baby sturgeon in Windsor

Young sturgeon in a dark tank. Photo by Pen Roberge.

In light of steady declines in lake sturgeon populations across North America, the University of Windsor, in partnership with the Great Lakes Institute For Environmental Research (GLIER), has begun a captive breeding program to try to restore lake sturgeon populations in the Detroit River.

In addition to producing baby sturgeon, the breeding program also aims to integrate the juvenile sturgeon back into the Detroit River so they will continue to reproduce, ensuring future generations will exist in the wild.

“They’re actually raising them in LaSalle right on the Detroit River in these tanks that range from essentially no background … to a very enriched tank with tons of rocks and other things that are more naturalized,” said Trevor Pitcher, a University of Windsor professor. “Then they’re comparing their behaviours, their stress and their swimming abilities to see which ones do best before we let them go in the future.”

Following their release, the research team tracks the fish. “A lot of times all the fish have tags in them, so we actually end up following them for essentially decades after the program,” Pitcher said. “These guys have kept their ancient form for that long so they live a long time, partly because they’re large and they’re slow growing.”