A school of ciscoes.

Schools of ciscoes shimmer under the light of day, beneath extraordinarily cerulean waters. Meanwhile, deep undersea, the lake bottom lies ominously eclipsed by an over-populous mollusc: the quagga mussel.

The quagga mussel is a rapacious filter feeder that is altering the food web within the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence freshwater ecosystem at an alarming rate. As they filter the lake water, they remove exorbitant amounts of plankton from the basins, clearing the water column substantially. The upcoming documentary All Too Clear explores the impacts these tiny molluscs are having on our freshwater ecosystems.

Biinaagami sat down with producer Yvonne Drebert and director/cinematographer Zach Melnick at their home on the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula to learn more about the behind-the-scenes efforts in making the upcoming documentary All Too Clear, while discovering a shipwreck in the process.

On quagga mussels as the chief character

Quagga mussels coat a tire on the bottom of Lake Ontario.

Zach: A few years ago, we were working on a series called Striking Balance about Canada’s Biosphere Reserves. We actually did an episode on the Georgian Bay Biosphere and that was when we were first alerted to this huge change happening in the offshore region. The places where most people don’t go in the Great Lakes. We learned through the folks at the Ministry of Natural Resources, and the organisation Georgian Bay Forever, that there are carpets of these little guys down on the bottom of our lakes and almost no one sees them. But they are having this tremendous ecological impact on the Great Lakes —one of the biggest impacts since glaciation.

We’ve lost the ability to control nutrients in the Great Lakes because of the quadrillions of these little guys who can filter up to seven litres each, every day. It’s a huge change that almost no one knows about because we don’t live underwater. We wanted to show people that this change has happened and explore what, if anything, we might be able to do about it.

Yvonne: Just to clarify — there are literally quadrillions of invasive quagga mussels in our lakes. There’s so many that, once a week, all of the water in Lake Michigan and Lake Huron is filtered through a mussel.

When I was a kid, zebra mussels came into the lakes. I remember them on the shore — cutting my feet on them where we used to swim in Lake Erie. But what actually happened is the zebra mussels have been outcompeted by quagga mussels.

Zebra mussels and quagga mussels are cousins, and they’re from a similar part of the world — where they originated — Ukraine and Russia, the Black Sea area. We think that they both came to the Great Lakes through ballast water and ships, and that the

Zebra mussels were here first and the quagga mussels followed shortly thereafter.

On partnerships and “technological revolutions”

A close-up of a mussel colony.

Zach: Up until a few years ago, the predominant problem you heard about in the Great Lakes is too many nutrients from runoff of agriculture and cities causing eutrophication — too many nutrients in the Great Lakes. As filmmakers, you just don’t want to tell the same story over and over again and you’re looking for a unique way to look at some of these things.

Once we learned that this big change was happening out there, we cast a wide net, starting here [in Lake Huron]. We made a pretty good partnership with the Sault Tribe in northern Michigan that have the rights to fish commercially in Northern Lake Huron, in Northern Lake Michigan, and Southern Lake Superior — they’ve been hugely impacted by this. But they [also] have a very robust science and fishery program and some decent resources to try to tease out what’s going on and find ways to help — especially the lake whitefish, which is a hugely important species for them. Along with them, we’re working with maybe a dozen or so science folks who are trying to do something about the problem and weaving those two narratives together.

The real main characters are the fish underwater and life underwater, so we’re really trying to bring to life some of these species that people haven’t been able to see and live with before.

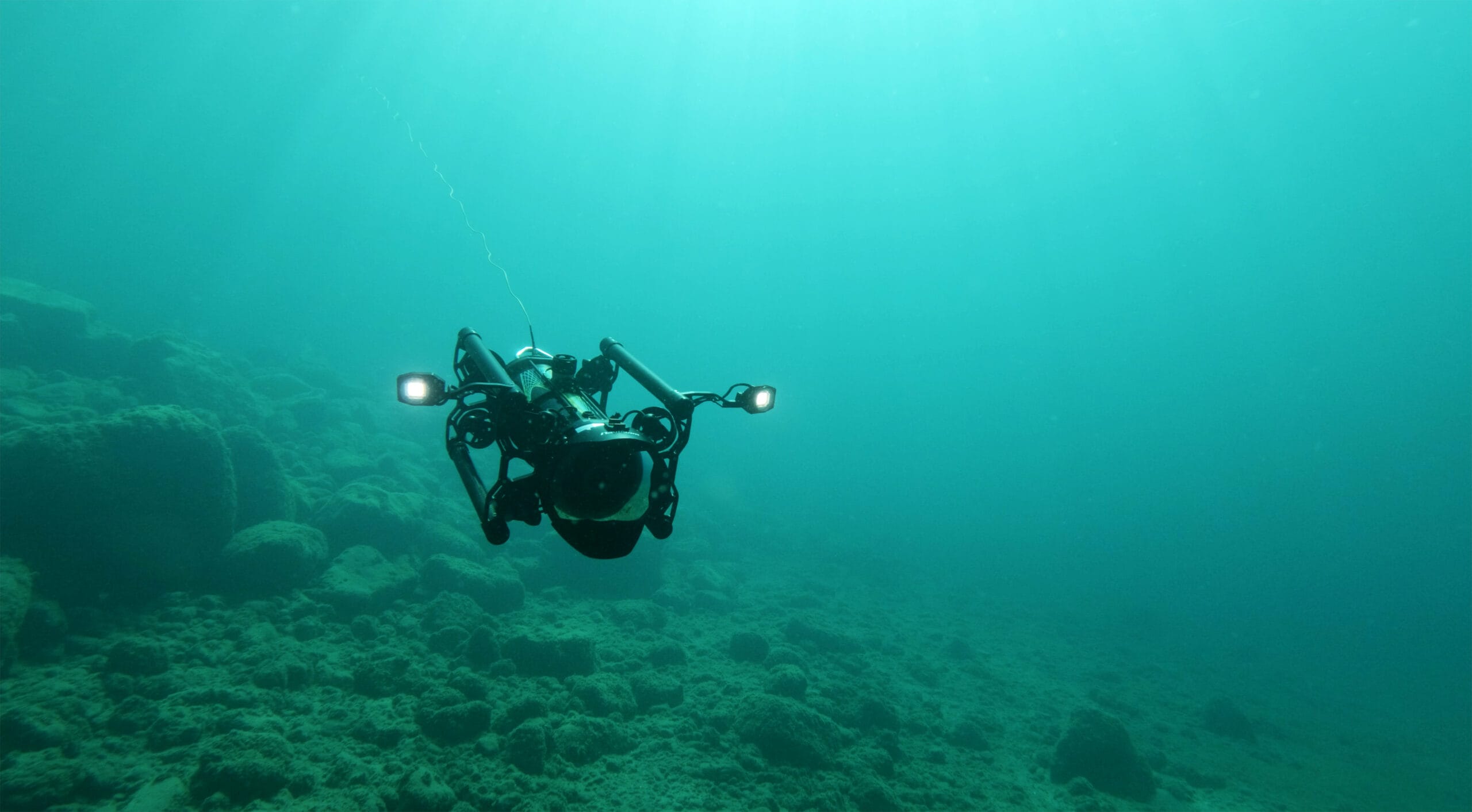

Yvonne: At the same time, there was also kind of a bit of a technological revolution in terms of underwater drones or [remotely operated vehicles]. Think of an aerial drone but underwater. So, we started playing around with [them] and we actually partnered with the world leader in underwater drones for cinema, a company in New Zealand.

Zach: We brought the first Boxfish Luna — a high-end underwater drone system — to Canada to work on this project. And we’ve been working closely with Boxfish Robotics, the company that makes the unit, and they’ve been improving it as we’ve been working on this system based on our feedback. So that’s been very exciting.

On how they captured underwater shots

The ROV Zach and Yvonne used to film underwater.

Zach: We didn’t know if we’d be able to get shots of really any of the species that we were trying to film underwater when we started this project. But then we just kept getting success after success using this technology.

Mussels are very small. So, we have been both filming them with the underwater drone and we’ve also been filming macro shots of them too. For very close-up shots, using macro lenses so we can see them feeding and their little mussel babies coming out.

We’ve also done a bit of microscopy. So we’ve been filming Zooplankton with that because this story is about the whole food chain, but especially, it’s about the bottom of the food chain. For instance, one of the creatures who has been most affected by this shift that’s gone on in the Great Lakes is a little shrimpy guy called the diporeia. This used to be the number one food item for Lake Whitefish. There were thousands of them per square metre, buried in the mud. They’ve been replaced by mussels, which are much harder to eat and digest for important species like the lake whitefish.

On how filmmaking and science collide

Yvonne: A lot of fish science, unfortunately, uses netting. Scientists are studying fish that have [often] died. And there is some necessity for that. But with our [remotely operated vehicle], we’re able to spend hours at a time with a school of fish. So, we’re able to see fish behaviours in a way that our scientific partners have never seen before.

On discovering the Africa shipwreck — and what they hope for the future

“The Africa” shipwreck entombed by quagga mussels on the floor of Lake Huron.

Yvonne: We discovered a shipwreck back in June 2023, which was completely entombed by quagga mussels. And we didn’t really consider the cultural heritage impact that the species could have before discovering the wreck. For us, it really was all about the ecology and the environment. It really goes to show [that] invasive species — their impact is so much greater than you can ever imagine and one of the reasons we really need to be mindful about how we’re transporting animals and plants around the world. You never can even imagine what all the impacts are going to be.

There is a bit of a silver lining to this story which really surprised us because, at first, when we started digging into it, it felt like a pretty doom-and-gloom kind of situation. But what’s happened as a result of the quaggas is that a lot of non-native species that are living in our lakes — they’re actually having a harder time in this new world created by the mussels than some of our native fish. A lot of those populations, especially in Lake Huron, have really dropped off. And what that’s done is created a space in the ecosystem that we could potentially help fill with native fish that belong in this kind of ecosystem.

There’s a group of fishes called ciscoes and that includes chub, lake herring, bloater — you know, all these fun names — that used to live throughout the Great Lakes and were fished out pretty intensely, historically. But now there’s that space out there that we could potentially fill with these fishes that like a lower nutrient environment than a lot of the non-native species. That is kind of exciting and there’s a few projects right now that are trying to do just that in the Great Lakes.

Zach: If there’s one thing that I would like to see come out of [All Too Clear] is a little bit of extra support for the notion of restoring river run white fish. One of the projects that the Sault Tribe is working on with Nature Conservancy is trying to figure out a technique for restoring the ancient, lost, forgotten river run spawning white fish populations. Historically, white fish would have gone upriver to spawn. Because the rivers, unlike the main lakes, have a lot more nutrients — a lot more life — in them because they don’t have the mussels there. But because we put in all the dams and we added sawdust to the river — like way long ago when the areas were logged — virtually all of those populations were wiped out. They’re starting to restore themselves a little bit to some of the rivers in Green Bay, Wisconsin. And so, these fish are coming back to spawn in the rivers of Green Bay for the first time in over a century.

Yvonne: I’m not sure that we’re ever going to eradicate quagga mussels from the Great Lakes. I don’t know if that’s going to be a possibility. But I am really heartened by the fact that the species that belong here, those native fish — this world might be a good world for them. That’s really hopeful for me.