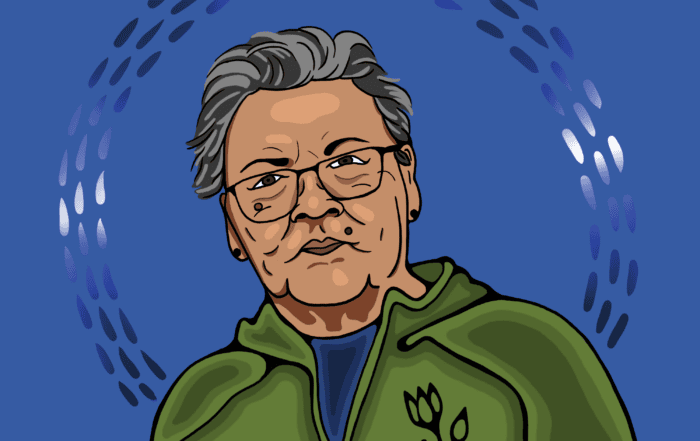

Valérie Courtois gives a TED talk on how Indigenous Guardians protect the planet — and humanity. “If we take care of the land, the land takes care of us.” (Photo: Valérie Courtois speaks at the Nia Tero TED Salon: Thrive. TED World Theater, New York. September 22, 2022. Photo: Gilberto Tadday/TED.)

Valérie Courtois is just looking to save the world, she says with a chuckle. No biggie. But the director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, who is a professional forester and member of the Innu community of Mashteuiatsh, has spent her whole life thinking about risk. “We cannot affect our environment to a point where we’re hindering the opportunity for future generations,” she says emphatically. As a forester, she looks at the boreal forest and thinks about its economic importance but also what needs to stay to ensure the forest — along with the wildlife and nations who depend on it — continues to thrive. This philosophy is part of why Indigenous-led conservation is vital for the preservation of biodiversity. And now Courtois is bringing these ideas to the world stage, from global conferences to a recent TED talk. She spoke with Canadian Geographic’s Explore podcast in the run-up to the UN’s COP15 biodiversity conference, held in Montreal this past December.

On Nitassinan, the boreal forest and caribou

Nitassinan is the Innu word for “our land.” “Assi” is the name for land. We’re in the easternmost extent of the boreal forest, which is the largest intact forest left on the planet. It is a caribou landscape, which is why my people are here. We are a caribou people. The George River herd — which occupies most of the Quebec-Labrador peninsula — has been essential to our story of why we’re here on this landscape. Our understanding of our place in the world revolves around that relationship. In fact, much of our food security historically has also depended on that herd. It’s essential for our nations — and not just the Innu Nation of which I’m a member, but all of the nations that depend on caribou — to figure this out and work hard to ensure that that relationship continues in perpetuity.

On Indigenous Guardians

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative supports Indigenous Guardians programs and other Indigenous-led conservation work. Indigenous Guardians are like our boots on the ground. They’re people whose job it is to take care of our landscapes, to ensure that our traditional laws are applied, that our communities are well informed of what’s going on, that the nations have a strong voice in considering the pressures and options and opportunities that come to them. Guardians in some ways are good development enablers. They can ensure that the communities are well informed when making decisions on what happens on their landscapes, and can therefore offer their free, prior and informed consent. My perspective is the more information, the better. And Guardians help do that. Being a Guardian is also an incredible career path. It’s one where you can fully integrate your culture within the expression of your career and your job. That’s incredibly attractive, especially in remote places that don’t necessarily have a lot of economic opportunities.

On Indigenous-led stewardship

We’ve been conservationists ever since we’ve existed. We understand that our relationship with our landscapes is what ensures our survival. We also know that gives us responsibilities to that relationship. That’s what is really driving this conservation movement. The International Boreal Conservation Campaign, which the Indigenous Leadership Initiative is a member of, has been supporting and working with First Nations across Canada for about 20 years. And what we’ve seen is that the vast majority — over 90 per cent — of new protected areas that have been established in that time have been either led or co-led by Indigenous Peoples. We’re also seeing the impacts of the work of the Guardians: in the last five years, that movement has more than quadrupled in First Nation communities.

On Canada as a leader

We have a particular responsibility to show leadership. If Canada can get it right, by truly empowering Indigenous nations to take on that [stewardship] role, then Canada can show the way on what it looks like to value the communities within its borders, the knowledge systems and sciences that contribute to everybody’s prosperity.

On what gives her hope

Guardians give me hope every day. It gives me hope when I hear mothers say: “I hope my son or daughter will be a Guardian when they grow up.” It gives me hope to know that there are people who are working hard to learn their language — that’s exciting. The explosion of Indigenous crafting online… all of this is possible because people are returning to the land and are able to source those materials and have the space and time to develop them. The fact that we’ve got more people going through post-secondary education, building, growing and asserting their leadership in the Indigenous community — all of this is exciting. We’ve had more women as Grand Chiefs than ever. Also, seeing how young people are experiencing what the Elders have told us about: when you go to the bush, you feel love. When you think about the dark colonial period that we’ve gone through, these kinds of things are certainly what motivates me. And I hope that other Canadians also see hope in that. Here in Canada, that bright light of Indigenous assertion and power and care for our lands is something that gets me out of bed in the morning.