I’m on my way to meet the sea when I hear the voice. It’s faint at first, a few stray notes climbing on the mist from a waterfall. As I approach the precipice creating the cascade, I see a human on a rocky outcrop. Wearing a red and green bonnet of the type Innu women have worn for centuries, she’s beating a drum. She sings. I’ve heard this chant before, especially in the time since humans with pale faces and neckties started coming to these forests with plans to divert me and other rivers. They said it was for progress. But for me, my progression was slowed down the moment they led me into that concrete box with sluices. Who is she pleading with, this sister? Then I hear it. She’s singing a healing chant — for me, the river — for all of us, for the planet. I hear, even though my voice is louder than her words. I roar. That’s how I know I am.

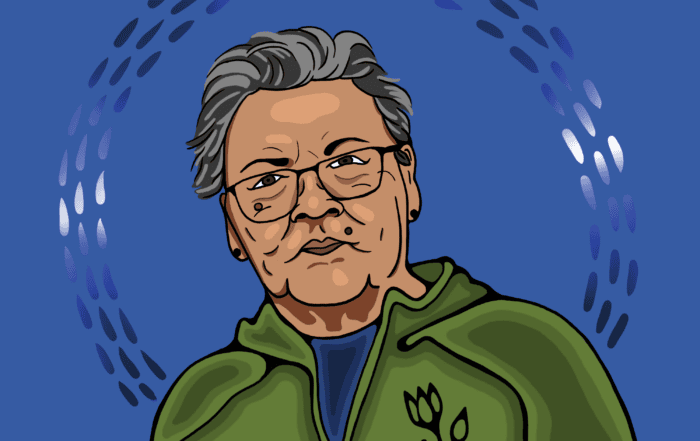

“We’ve always known the river is alive. Our ancestors have always said that,” says Innu activist, poet and educator Rita Mestokosho as she swaddles her deerskin drum in a fleece blanket. “The river is like the blood that runs in our veins. If the river is sick, we will also be sick. That’s why we need to protect her.” The waterway she’s talking about is the Mutehekau Shipu (spelled differently in different dialects of Innu-aimun), also known as the Magpie River, a nearly 300-kilometre ribbon that swirls through a pristine area of the Côte-Nord region in eastern Quebec. For Mestokosho and the people of Ekuanitshit, an Innu community located on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the river has always been family. In February 2021, the world was introduced to Mutehekau Shipu when the people of Ekuanitshit and the regional municipality made a joint declaration granting the river legal personhood and rights — the first resolution of its kind in Canada.

Mutehekau Shipu’s personhood declaration applies only to the waterway, not the watershed, something the locals hope to change in the future.

The province’s mightiest rivers have already been dammed (or damned, depending on who you ask) by Hydro-Québec, the fourth-largest hydro-power producer on the planet, but the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit, the community’s governing body, hopes the Mutehekau Shipu’s personhood status will keep her safe from a similar fate. “The difference now is that the other people in the region also stood up,” Mestokosho says. “This time, we stood up for the river together.”

The “other people” who joined the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit in their defence of a free-running Mutehekau Shipu are the Minganie regional county municipality, SNAP Québec (the province’s chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society), and the Association Eaux-Vives Minganie, a group of nature-lovers and paddlers. Together, they make up the Muteshekau-shipu Alliance. Their goals are to protect the river through the personhood declaration; assign stewardship to Indigenous Guardians who will monitor its well-being; and designate representatives to carry the river’s voice to community members and uphold its rights in boardrooms and courtrooms.

While it’s a local initiative involving the direct participation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous land defenders and decision-makers in Côte-Nord’s St. Jean region, the personhood declaration of the Mutehekau Shipu carries broader implications. In a global context, it’s part of a slowly growing, mostly Indigenous-led movement that aims to turn corporation law (which grants corporations — from businesses to churches to NGOs — legal rights comparable to those of persons) on its head by recognizing the rights of nature and holding governments, corporations and other actors accountable.

Map: Chris Brackley/Can Geo; Map data: Shelters/Forest Management Unit/Hydro Corridor: Proposed biodiversity reserves for the massif of Lakes Belmont AND Magpie, the knolls of Lac aux Sauterelles, the foothills of Lac Guernesé, and the Collines de Brador. Government of Quebec, 2007.; Mining claims: https://gestim.mines.gouv.qc.ca/ftp/cartes/carte_quebec_eng.asp#2 (data time stamped Jan 10/2022)

On a national level, the declaration has the potential to stand as a precedent-setting victory, inspiring other Canadian jurisdictions to give nature the means to defend itself from industrial encroachment. After all, in a time that’s marked by the double shock of the climate and biodiversity crises, protecting nature by legal means may be one of the most effective ways forward for saving life as we know it.

For Lydia Mestokosho-Paradis, Rita Mestokosho’s niece, the Mutehekau Shipu provides a starting point from which life in Nitassinan, the traditional territory of the Innu, can flourish. “The river is a transportation route. We use it for drinking and cooking. It’s the pharmacy, it’s the pantry,” she says.

Mestokosho-Paradis is sitting so close to the Magpie Falls, or the Third Falls (so-called because it’s the third waterfall upriver from the sea), that she can feel the mist on her face. It’s as if the river is breathing. She runs a hand over the smooth rock. A visual artist and cultural interpreter at the Maison de la Culture Innue in Ekuanitshit, she’s come here with her aunt to honour the river and their ancestors, following a tradition of showing all living beings that you remember and care about them. The personhood designation, she hopes, will prick the consciences of those who want to stem its flow. “They don’t understand the vision that the river is alive. But how can you see a corporation as a person, an entity with moral rights, and not see a river in the same way?”

If they still don’t get it, she urges them to come and see for themselves. “Bring your children, your wife, your husband; look at what this place is. People in government need to come here before making decisions,” she stresses. As if to underscore her point, the sun pokes through the clouds, spilling enough light to draw a rainbow in the mist. “Do you really want to be the person who destroyed ancient portages and animals and their habitat for money?”

Early morning is my favourite time of day. That’s when the Labrador tea lets its dew-drop cloak slip from its leaves, soaking the air and the caribou moss at its feet with a fragrance that reminds me of spruce resin. It’s also when moose cows and their calves come by to drink. Travelling this route in the morning opens my senses to the rhythm that divides the night from day, but it’s only later that there’s enough light to make out the old portages that have brought people to me since time immemorial. In the afternoon, ravens call out to one another — and perhaps to other animal spirits — from the trees. They swoop and soar, playing in the wind like I play among the rocks. I slow down for a closer view of the mountainside, where aspens wave their golden hands at the sombre spruce. As the daylight starts to fade, I wrap myself in pastel scarves unfurled by the sky: pink, orange, yellow. The evening flatters me.

Lydia Mestokosho-Paradis says protecting the river also means protecting medicines, like Labrador tea (below), which have been used since time immemorial.

The sun is getting ready to slide behind the treetops when Sylvain Roy arrives at his hike-in chalet on the Mutehekau Shipu. An avid whitewater paddler and plein-air enthusiast, he started coming here in the 1990s as a paddling instructor at a Montreal canoe club. The river soon became a favourite destination for whitewater excursions; it was on one such getaway that he decided to do a side trip, hiking upstream until a roaring sound led him to a constriction in the river: the Magpie Gorge, or Fourth Falls. The moment he saw the river crash through the canyon, then shapeshift into a slow-moving, swimmable basin downstream, Roy was sold. Power and serenity coalesced in a single gesture cradled by hills made rugged with a stubble of spruce. He knew immediately he wanted to wake up here on as many mornings as possible for the rest of his life.

But some of the characteristics that make this the perfect spot for Roy’s rustic, off-grid cottage also make it vulnerable to exploitation. “The biggest threat to the river is Hydro-Québec,” says Roy. As he pours hot water for coffee, the rising steam mimicking the spectacle outside, he explains that the Mutehekau Shipu is blessed with an abundance of whitewater thanks to its tumbling down a particularly steep gradient of the Canadian Shield. He nods toward the gorge, where the flow is so dangerous that outfitters taking guests on weeklong expeditions portage to the basin below. If a dam were to be built downstream of his cottage, Roy’s hilltop chalet might remain above water, but the access trail and most of the lot would be inundated. It would spell the end to fishing from nearby islands and picnicking by the waterfall; it would deport the moose cows and their calves to unknown territories.

Hydroelectric projects are a constant threat. Built in 1961, the only existing generating station on the Mutehekau Shipu strangled the First Falls just north of Highway 138. It was upgraded in 2007 to increase its energy output; the expansion flooded a section popular with whitewater kayakers, including Roy. Then, in its 2009-2013 strategic plan, Hydro-Québec targeted the river for a hydroelectric “complex” that would churn out some 850 MWh, enough electricity to power roughly 290,000 homes. That scheme — and the spectre of the massive, four-dam project that had just broken ground on the Unamen Shipu (commonly known as the Romaine River), an hour and a half’s drive east on the 138 — set off alarm bells among Innu, paddlers and environmentalists.

The community of Ekuanitshit.

Sylvain Roy makes coffee at his cottage by the Magpie Gorge.

River protectors of all stripes staged a flash mob outside Hydro-Québec’s head office in Montreal in September 2017, demanding an end to all future plans to dam the river. The utility responded by taking Mutehekau Shipu out of its near-term proposals but made no promises for the future (as of September 2021, it still wouldn’t rule out a hydroelectric project on the river). While the Innu, the Minganie regional county municipality, SNAP Québec and Eaux-Vives had already built consensus around a common vision for the river, it was a lack of commitment from Hydro-Québec and the provincial government that prompted the creation of the Muteshekau-shipu Alliance in 2018. “We wanted to create a protected area, including the river,” says Pier-Olivier Boudreault, SNAP Québec’s conservation director and one of the alliance’s de facto coordinators. But, says Boudreault, because protected areas, such as national parks, wildlife conservation zones and migratory bird sanctuaries fall under governmental jurisdiction, “we decided to take matters into our own hands and use the tools at our disposal.”

That made sense, considering rivers, with their strong cultural and spiritual significance to Indigenous Peoples, are at the vanguard of the most important rights-of-nature legislation that has been passed internationally. In Ecuador, a lawsuit by residents of the Vilcabamba River stopped a harmful road construction project in 2011. In Colombia, a court decision based on the country’s constitution protected the Atrato River from mining. And New Zealand’s Whanganui River was declared a legal person in 2017. After studying these and other examples, and with no movement from Hydro-Québec and the provincial government, the alliance decided the best mechanism for protecting the Mutehekau Shipu would be legal personhood. As a complementary tool to this declaration, the alliance is working to have the river recognized as an Indigenous protected area.

For Rita Mestokosho, Innu rights and the rights of nature go hand in hand.

Mestokosho’s patch commemorating the 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation in South Dakota, which fought for Indigenous treaty rights.

The Muteshekau-shipu Alliance called on the International Observatory on the Rights of Nature, a Montreal-based non-governmental organization that offers legal advice and does policy research with a focus on securing legal rights for nature, to draft a 15-page resolution to declare the river a legal person with nine rights, including the right to flow and the right to sue. Boudreault explains that to create the final resolution, lawyers from the International Observatory used case law that cited the precedents set by previous rights-of-nature cases such as the Vilcabamba and Whanganui rivers. But because the Canadian Constitution doesn’t enshrine rights for nature as a legal entity the way it upholds rights for humans and corporations, Boudreault cautions that “there could be legal challenges to the personhood status.”

David Boyd understands better than most people how complicated rights-of-nature cases can be. A UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment and an environmental law professor at the University of British Columbia, he is “cautiously optimistic” the resolution could be a game changer for the Côte-Nord region — and for the rest of Canada if the precedent is set. “It’s groundbreaking in a Canadian context; it’s revolutionary,” he says. “But it’s difficult to say how revolutionary; it’s impossible to say at this point how courts will interpret the law.” While it passed in both the Innu and municipal councils, giving it legal protection, it’s not directly on par with Ecuador and Colombia, where nature has constitutional status. Still, says Boyd, “Hydro-Québec would be taking a great risk if they think they can proceed with a dam under this law.” Canada’s “Protection of Aboriginal Rights” provision in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 may confer constitutional status on Mutehekau Shipu’s personhood declaration. And the country’s adoption in June 2019 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), though not legally binding, spells out Canada’s commitment to free, prior and informed consent — conditions that imperil a hydroelectric power project on the Mutehekau Shipu.

Mutehekau Shipu, seen here at Magpie Gorge, or the Fourth Falls, means “the river where water flows between square rocky cliffs” in Innu-aimun.

But Boyd also makes clear the law is revolutionary from a cultural perspective. “Canadian culture has — with the exception of Indigenous Peoples — treated nature as property. This declaration is saying very clearly that that is not the worldview of Indigenous People and it shouldn’t be the worldview of Canadians in general,” he says. “Nature is far more than just a basket of resources; it’s an extraordinary, wondrous community that we’re incredibly fortunate to be part of. All Canadians need to rethink our fundamental relationship with nature if we are going to achieve a sustainable future.”

I love the feeling of flying over the land, of skimming the bedrock and using it to leap, reaching for the sky. This freedom allows me to speak with the frankness of thunder (that’s how I know I am). I laugh when the boulders invite me to wrestle them because, if you ask me, I usually win. But I also feel sad sometimes, especially when I think of my sister, Unamen Shipu, whom the newcomers insist on calling La Romaine. She doesn’t fly anymore, her silver wings clipped and silent. Remembering her is important; remembering is a survival skill. That’s why I decide to commit to memory this October morning when a helicopter lands on one of my islands. Out step a young woman and the Chief who leads their village; I’ve seen them both before. She takes a seat on a log I tossed on this little island for her ancestors to sit on many years ago. Her voice is clear, a blue sky that could stave off any storm, “The word Innu means ‘human being’; we are all Innu. We stride forward on one single portage, and we need to stay united to stop individualism and colonialism — to stop breaking the planet. We are only passing through here.” It gives me hope to know she’s got my back. She’s got all our backs. I’m free to meet the sea.

Shanice Mollen-Picard closes her eyes. Wrapped in silence, the sun lapping her face, she lets the river trickle into her mind. “I hear the water. I hear the river say shhhhh. I hear that she’s alive,” she whispers. “I hear fish under the surface. And there’s a mystery. I always wonder, is it a salmon?” For Mollen-Picard, an Ekuanitshit resident and a coordinator for the campaign to personify and protect the Mutehekau Shipu, that mystery would become a nightmare if an industrial project were to block the salmon from swimming upstream and stop rafts from floating with the current. Through fishing and rafting, the Mutehekau Shipu has provided her and other Innu a way to reconnect with the land in a time when the legacy of colonialism and modern technological distractions have robbed them of those links. “I want youth to be able to keep paddling down this river,” she says. “I want my son to be able to fish here in the future.”

To keep people and fish going with the flow, the river’s personhood resolution includes the creation of an Indigenous Guardian program, in the works by Mollen-Picard and the rest of the Muteshekau-shipu Alliance. “The Guardians will be our eyes and ears on the land; they’re going to gather data on fluctuations in the water, climate change and what species they see,” Mollen-Picard says, adding that the Guardians will also look for evidence of caribou, a species the Elders used to see around here. She believes the future of economic development in the region lies in recreation and tourism, not hydroelectricity, with the river being a key driver. She stresses that a dam here would destroy the last powerful river in Nitassinan, recalling how the Unamen Shipu has been lost to the Romaine hydroelectric project. “The portages our Chief once did are no longer accessible. He saw the river before the changes, before flooding destroyed habitats for animals. The animals have left, the trees have fallen — and yet people say the project had no negative effects.”

Shanice Mollen-Picard hopes her young son will be able to fish and canoe on a free-flowing river.

The only generating station on the Mutehekau Shipu is at the First Falls, near the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The Chief she’s talking about is Jean-Charles Piétacho, who has led the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit since 1991 (he was re-elected in September 2021). He’s been standing by, listening to Mollen-Picard and the river. For him, nature is where the heart is; it’s home. When the Romaine project was announced, he and a group of Elders set out to record the portage routes that would be flooded — to write history and commit their home to memory through interviews with Elders and research. “We also had this idea to redo the portage routes, to know where and how our ancestors travelled. So my aunt, a group of Elders and I went on the river for two and a half months,” he says.

The group of 15 went as far as where the fourth dam is today, doing 67 portages along the route, including one that took them a whole day. “It was a good trip; we learned and found portages and places where people had cabins and where they used to meet. Those are all inundated now,” Piétacho says, adding that the Romaine project did little for the Innu of Ekuanitshit; its only legacy is a trail of destruction. Politicians and representatives of Hydro-Québec said it would develop the region’s economy and infrastructure. “We were promised jobs, money, contracts, but that didn’t materialize on the scale we hoped. The energy is not for us, it’s for sale,” he says, referring to the complex’s output being largely for export to markets outside Côte-Nord and Quebec. “That’s why environmental protection now is more important than the economy. We don’t want the Mutehekau Shipu to become another Romaine.” Remembering becomes a survival skill for people and rivers alike.

Jean-Charles Piétacho, Chief of the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit, has seen the ravages of hydroelectric projects on other rivers and is determined to keep Mutehekau Shipu safe.

For the Innu of Ekuanitshit, Mutehekau Shipu is a sister who carries and uplifts the voices of the ancestors. They insist the river must not become “another Romaine.”

Piétacho and Mollen-Picard climb into the helicopter that dropped them here. As its rotors pick up speed, they push the water out from the island, creating a halo of droplets. It’s fitting for a river — an entity, a person — who’s sacred to so many, as an ancestral home, a place to connect with nature, a life source, an adventure destination. From high above the Mutehekau Shipu, Piétacho leans his head against the helicopter window. Tracing the river’s path across the landscape, he reads her message that it’s crucial to remember. He doesn’t look away until the helicopter veers east toward Ekuanitshit. It’s as if he’s etching the river’s shape in his memory. There, she will always be safe, flowing freely across the land.

RIGHTS OF THE RIVER

It took two years of back-and-forth between the Muteshekau-shipu Alliance and the International Observatory on the Rights of Nature to finalize the resolution that grants legal personhood to the Mutehekau Shipu. The document details nine specific rights:

- to live, to exist and to flow

- to respect for its natural cycles

- to evolve naturally, to be preserved and protected

- to maintain its natural biodiversity

- to maintain its integrity

- to perform essential functions within its ecosystem

- to be free from pollution

- to regeneration and restoration

- to take legal action

NATURE’S LAW

The Canadian Constitution’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not include nature, something that would have strengthened the Mutehekau Shipu’s personhood declaration. How does Canada stack up against other jurisdictions when it comes to enshrining the rights of nature? We asked David Boyd, the UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment, for the three strongest examples globally.

NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand has passed two laws in favour of nature: the rights of a river and the rights of an ecosystem. The legal personhood of the Whanganui River was formalized in 2017, three years after the Te Urewera ecosystem was granted the same rights. But what’s most exciting to Boyd is that “things are effectively changing on the ground in New Zealand — they’re moving forward with implementation.” The legal personhood granted to Te Urewera and the Whanganui River, as well as to Mt. Taranaki in the Whanganui watershed, are a reality thanks to a government commitment to reconciliation through adopting Maori traditional knowledge and worldviews.

ECUADOR

In 2009, Ecuador became the first nation in the world to protect nature in its constitution. While the country is still mining and drilling for oil and gas, Boyd says this dramatic recognition signals hope. Because of its constitutional status, “it’s the highest and strongest rights-of-nature law in any country,” he says. A 2014 amendment to the criminal code included crimes against Pachamama (Mother Earth), and 2016 saw a further legislative strengthening of the rights of animals and nature. In 2021, Ecuador’s constitutional court upheld the rights of nature by banning mining in a protected forest area.

COLOMBIA

To reverse the heavy pollution and damage inflicted on Colombia’s Atrato River by illegal mining, the country’s constitutional court in 2016 declared the river a legal person with rights to, among other things, protection, conservation and restoration. And in 2018, the Supreme Court of Colombia recognized the Amazon ecosystem as a legal person. “Colombia is exciting — it’s a place where there have been at least 10 different court cases that have recognized the rights of nature,” says Boyd. “Now, they’re in the process of working out what that means and how it’s going to change people’s relationship with nature.”