Perhaps it’s the imposing cliffs that surround it, or the saturated colours of its sunsets and storms. Perhaps it is its sheer size. Whatever the reason, Lake Superior — in particular the 550-kilometre stretch of shoreline between Sault Ste. Marie and Thunder Bay — has held a particular fascination for artists since before Canada became a country.

In a story that appeared in the December 1986 issue of Canadian Geographic, Celia Ross surveys various paintings created over a period of more than a century and suggests that Lake Superior poses an irresistible challenge — one that pushed some of Canada’s most notable painters to produce the best work of their careers.

“Our artists have had to mature and struggle over the years to meet the challenge of depicting this wild landscape,” Ross writes. “The story of their efforts turns out to be a capsule history of the development of landscape art in Canada.”

Here is a look at some of the most noteworthy depictions of the largest of the Great Lakes:

“Sault Ste. Marie” by Paul Kane, circa 1846. Kane was among a number of naturalists who ventured to the north shore of Lake Superior in the mid-19th Century to study and sketch its flora, fauna and indigenous inhabitants. Artists like Kane who painted aboriginals “were partly seeking to document a way of life fast disappearing,” Ross writes. The construction of locks and a canal at Sault Ste. Marie in the late 1800s would open Lake Superior to increasing ship traffic and rapid settlement of its shorelines. (Image: Paul Kane/Royal Ontario Museum)

“Thunder Cape” by William Armstrong, 1867. Armstrong’s works are in the picturesque mode — that is, they highlight the drama of the landscape while still showcasing something of the local way of life (in this case, the people in canoes add an element of human interest). By the late 19th century, settlement and increased ship traffic meant Lake Superior no longer seemed a forbidding wilderness, and travel books of the time used paintings like Armstrong’s to encourage Canadians to explore the beauty of their country. (Image: William Armstrong/Library and Archives Canada)

“October on the North Shore, Lake Superior” by Arthur Lismer, 1927. “‘Serious’ painters spent the last years of the 19th century and the start of the 20th experimenting with different European styles of painting … attempting to portray Canada as a piece of England or France,” Ross writes. Not so a group of young Canadians who, in the 1920s, broke with artistic convention and went north in search of landscapes with a strong character. The works of the Group of Seven have had an indelible influence on the way Canadians – and the world — see Canada. (Image: Arthur Lismer/National Gallery of Canada)

“North Shore, Lake Superior” by Lawren S. Harris. Of the Group of Seven painters, Harris felt the strongest connection to Superior’s north shore. The uncluttered simplicity of the landscape allowed Harris to construct scenes “deeply satisfying to his mystic nature,” Ross explains. “All specific topographical detail is omitted. Stumps are painted without bark, hills without trees, water without waves. Light infuses the paintings with a spiritual quality.” (Image: Lawren S. Harris/National Gallery of Canada)

“Inland Sea” by Valerie Palmer, 1982. According to Ross, Palmer’s work exemplifies how modern realists faithfully reproduce a scene (right down to the exact copy of a 15th-century portrait of a lady that hangs on the wall), but still “succeed in making an inner quality visible.” (Image: Valerie Palmer/Canadian Geographic archives)

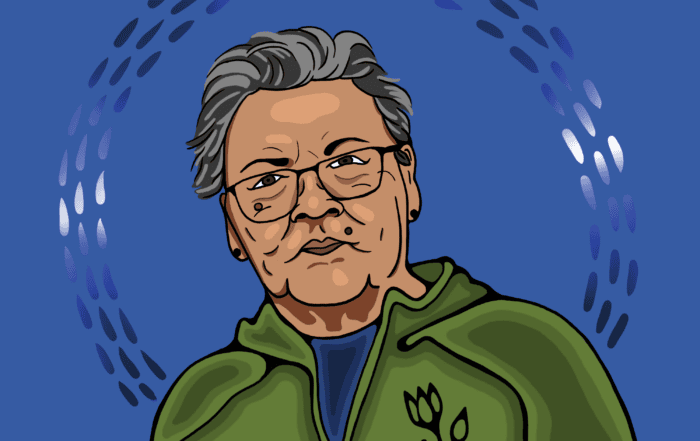

“Snow Spirit” by John Laford, 1977. Ross highlights several interesting features of this work by Manitoulin-born Ojibwa artist John Laford, including the way the landscape is present but mediated by mythical figures, and the rare perspective of the shoreline from the water. “The wavy lines linking the fish under the ice to the snow spirit indicates power relationships and the unity of the ecosystem,” Ross writes. “The sun is depicted low on the horizon and with little energy, while the cold winter moon rides high in the snow-flecked sky.” (Image: John Laford/Alan G. Gordon/Canadian Geographic archives)