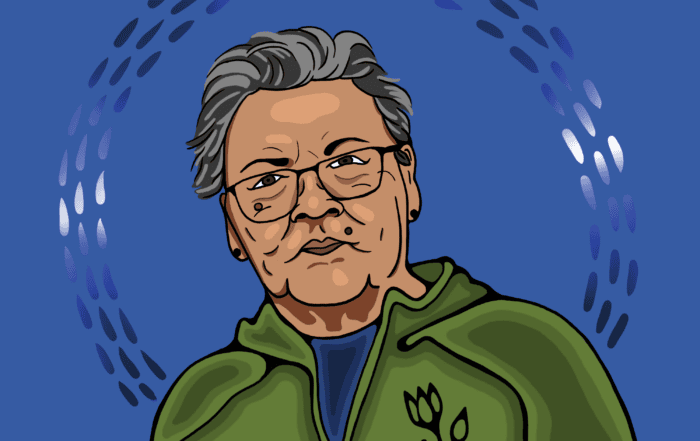

Cayuga Elder, Norma Jacobs. Photo by Colin Boyd Shafer.

Since the creation of the Kayanere:kowa, many Haudenosaunee annually retrace the Peacemaker’s journey for a recital of the Great Law of Peace; to remember and reaffirm those ancient commitments to each other and to the lands.

A Cayuga Elder sits inside the umbral light of a longhouse at Crawford Lake Conservation Area and shares her story to a small, captivated audience about her experience tracing the Peacemaker’s journey with a group of 40 others, as a younger woman. Her name is Norma Jacobs, or Gae Ho Hwako. “My mom told me that it means holding the canoe,” says Jacobs.

She describes the endeavour as a form of inquiry, “like doing research,” she explains. “I guess not in a way that academics do it, but just in our travels and having that experience of being on our land and following in the footsteps of the Peacemaker.”

The way of peace shared among the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy wasn’t always so. They were divided and at constant war until a prophet, in a stone canoe, paddled to all the villages of what is now southern Ontario and upstate New York, spreading the message of peace. According to oral histories, the Peacemaker’s grandmother had dreamed long ago that her daughter would have a son who would bring a message of peace from the Creator across the waters of the Great Lakes.

When that child became a man, he paddled across the water to the five warring nations and fulfilled his grandmother’s vision. With the help of Jigonhsasee — the first Haudenosaunee matriarch, and Aiionwatha (Hiawatha), the Peacemaker united the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca peoples in everlasting peace. Aiionwatha and the Peacemaker used Wampum to record the Haudenosaunee constitution known as the Kayanere:kowa — The Great Law. They also instituted the matriarchal clan system, the traditional chief system, and assigned roles to each of the original five Nations. In 1722, centuries later, the Tuscarora would join the confederacy as the sixth and final Nation.

To retrace the Peacemakers Trail today “is a revitalization of connection to the land; to learn about these sacred sites and to remember what it means to walk this earth as Ogwehoweh” — meaning Original People, says Jacobs.

Inside the Longhouse at Crawford Lake, where Jacobs would soon begin to share her story. Photo by Scott Parent.

The Peacemaker was born on Eagle Hill in Kenhtè:ke, a Mohawk village now known as Tyendinaga, on the shores of the Bay of Quinte, Ont. It’s where he began his mission of peace on Earth and remains the starting place for Haudenosaunee who wish to retrace his journey today.

“We started at Longhouse because we wanted to have someone to burn tobacco for us. So that we could have a safe journey for all of our passengers; and so we travelled to Tyendinaga.” Tobacco is a sacred medicine to the Haudenosaunee. They clench the dried leaves, imbuing them with good thoughts before casting the tobacco into a fire whose smoke will carry their messages to the Sky World.

One early morning, while camping near the bay, Jacobs stirs awake. “I could hear people and footsteps on the ground, and I thought, ‘who could be up so early?’ And so, I got up and I looked outside, and nobody was walking around, and everybody was still sleeping,” she recounts. She went back to her tent to lie down. But then “I just heard some sounds. Maybe it was dogs or something walking around, but they really sounded like human footsteps! She laid back down then all of a sudden, a great gust of wind came and almost lifted up her tent.

“Okay, I’m getting up!” she laughs to the wind.

“I think the most impactful [memory] for me was being connected with the spirits, with the ancestors, and feeling them travelling with us,” says Jacobs. That wind gust “was just the ancestors, you know, telling us to awaken now because we still had a long ways to go.”

Morning fog on O:se Kenhionhata:tie, Willow River, also known as the Grand River. Photo by Scott Parent.

Next, the group travelled about 400 kilometres to the southeast to Cohoes Falls. Looking back in time, Norma explains the Mohawk Nation there was initially reluctant to believe the Peacemaker was truly sent by the Creator and so they devised a plan to test him. The Mohawks challenged the Peacemaker to climb up a towering tree at the crest of Cohoes Falls. They intended to chop down the tree once he reached the top and “said that they would accept his word if he survived that fall.” The Peacemaker, knowing the Creator was on his side, accepted the challenge and allowed the Mohawks to plunge him over the falls and out of sight.

Jacobs explains, “a few days later, they went and here they seen the smoke rising from across the river.” The Mohawks saw the Messenger tending to a fire without a scratch and, true to their word, became the first to accept his message of peace. “He was being challenged, you know, to his truth and he was able to convince people that he did have this great message for our people.” The region is also historically significant as a place of strategic importance for messengers and warriors running between the different villages.

“I could just imagine how many runners had come through that place and how they gathered and would sit there and have their meal,” says Jacobs. Just as she would thousands of years later —feeling the presence of the old ones.

They continued to Oneida where they learned about the harm the battles between the English and the French had inflicted on the Confederacy. “From what I was told,” Jacobs says, “that was the last place that the Confederacy had come together to work together and to have a condolence for raising up the chiefs.” The condolence ceremony governs the succession of leaders while recalling the Peacemaker’s condolence of Aiionwatha. Having suffered the loss of his wife and daughters as a result of the bloody feuds between nations long ago, Aiionwatha fell into a deep depression and wandered aimlessly in despair. Until one day, the Peacemaker found him smouldering in his grief. The Peacemaker conducted a ceremony of condolence, to help Aiionwatha reconcile with his inner torments. The condolence of Aiionwatha is imbued in the Great Law of Peace; a remembrance of Aiionwatha’s great overcoming of loss and suffering while he sought a greater peace for all, each time a new leader is raised.

The Great Tree of Peace, a white pine, stands at Onondaga, the capital of Haudenosaunee territory. “You can still see that on a white pine tree, you’ll find a cluster of five needles,” says Jacobs, which represents each of the original Five Nations. “That’s really a powerful message for our people to think about — that our history is even recorded in this pine tree.” It is the chief symbol of peace and is often featured in Haudenosaunee artwork and clothing. Its roots run deep along the four cardinal directions across Turtle Island, extending the invitation of peace and harmonious relations to neighbouring Nations.

“I think that it’s another symbolism of our people, to look at the values of what the Peacemaker brought in order for us to create peace, which is working together and having compassion and understanding for each other and taking care of one another,” says Jacobs. “Sharing, you know, and having that strong belief in who we are.”

It is said that, when cut, the tree would either bleed or it would run clear. The Peacemaker said that if it ran clear, he was still nearby. If it bled, he was not.

Pinus Strobus, commonly called the eastern white pine, symbolizes peace among the Haudenosaunee.

“One of the things that impacted me the most is because it was taken away— our voice, by colonization,” says Jacobs. Only 55 people reported Cayuga as their mother tongue in Canada on the 2016 census, while fewer than 300 speak the language at all, with speakers mainly found in southern Ontario and New York state. UNESCO considers the Cayuga language as critically endangered.

For Jacobs, the journey across the Haudenosaunee territories evoked a personal transformation. Jacobs belongs to the Wolf Clan, one of nine Haudenosaunee clans that, like their animal namesakes, have their own roles and responsibilities. The Great Law determines how each clan relates to each other. The Wolf Clan are instructed to help others live in accordance with Haudenosaunee laws and values, something Jacobs carries with her.

“It tells me that I can fit into the landscape of where my territory is,” says Jacobs. “It’s there for us. And all we have to do is to reach out and to walk with our teachings so that we come to that place of understanding.” Encouraging others toward their own cultural revitalization.

By petitioning the ancient trail of their origin story, they unearth valuable teachings of healing through language and ceremony; about what it means to walk the earth as Haudenosaunee today.

They also learned that the stories of their ancestors are not just stories.

“We could feel the energy of the earth, you know, and our ancestors as well,” says Jacobs. “So it was really impactful to a lot of people. And I say that it changed our lives and the direction that they were headed in. Even my own son, Eric, said ‘I didn’t know this was real’ until we visited those sites.

He’d come to realise that, you know, especially at Cougar Lake when he said, ‘this place is really special’ and that’s where the Peacemaker uncovered the wampum.”

The People of the Longhouse have Aiionwatha to guide them. Aiionwatha has the Peacemaker. Today, the Peacemaker has Jacobs, knee-deep in the river with her hands held tight to the gunnels of his stone canoe. Upholding his message of peace and the teachings of the Creator.

“I think that on our journey as well, a lot of people had healing because of their contact with the spiritual realm and just having medicines available to be able to help people, like sage or even cedar — things that we use in our culture to be able to heal and to allow that time for them to grieve,” says Jacobs. “That healing comes from our Mother Earth.”

In the longhouse at Crawford Lake, Jacobs’ face swells with emotions in her closing reflections on the journey and what walking this path has taught her in life. Her audience sits in captive silence as she concludes how the teachings along the Peacemakers Trail have shaped her own story.

“To me, it always shows us the strength that we have, that’s built into our culture, to our ceremonies, so we can see it in our environment, that the Creator really thought we were precious enough to provide these things for us.”