The call of the loon is different. Wherever, whenever and however you happen to be reading this — on a crowded subway or home in bed, in a dentist’s office or on a beach, scrolling through your phone at work or waiting for a friend at a bar — if I asked you to remember the call of the loon, you could. The call of the loon endures. It is a sound like no other, and it lodges with us. Why? Why is the call of the loon so distinct from other birdsong, so fiercely memorable?

The endurance of the call of the loon in the mind is stranger when you consider that, unless you live by a lake or on an island on the West Coast, a loon cry is not a sound you hear every day. It is not, say, the song of a robin, which you might struggle to recall even though you’ve heard it every spring day your whole life. For people who live in cities — 82 per cent of Canada — a loon call is a sound they might hear, if they’re lucky, a few dozen times a year. Yet the sound palpably remains.

A male responds after being called back to its chicks when an intruder enters its territory.

When I remember the call of the loon, I’m thinking specifically of the wail, which is actually only one of its four distinct calls — the others being the yodel, the tremolo and the hoot. The yodel is a series of rising high pitches, not unlike a car alarm, which male loons make by jutting out their necks. It registers fear or danger or anger. The tremolo is a brief crazy laugh — loony — used to register intrusions into territory or the loon’s own presence: “Pay attention,” it says. The hoot is a short, delicate sound meant for nearby family, a soft “c’mere.” The wail is a pitch that rises and falls, an interval that falls off. The wail serves as long distance communication between mating pairs. It’s the sound of nature longing. As if the loons were trying to share something, not necessarily with us, but with the lakes themselves. It is a “here I am.” Here I am. Here I am.

The sound is there, and it has always been there. The loon is part of an ancient lineage of living birds — at least 55 million years old — and all five species are part of a primitive order found in the fossil record beside mastodons and sabre-toothed tigers. The loon was making the call you hear before great apes had evolved for us to evolve from. The call of the loon makes the puniness of the mere 300,000 years of Homo sapiens apparent. The sound was waiting for us, for you, from the beginning and before the beginning.

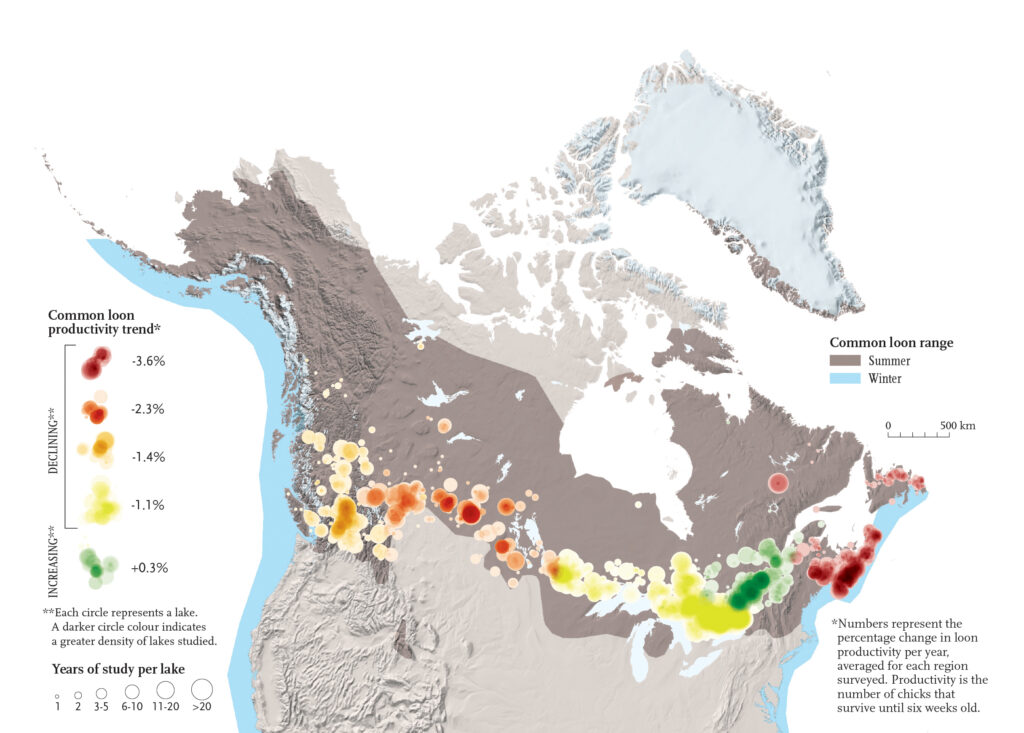

Map: Chris Brackley. Data: Lake Productivity Data: Birds Canada Canadian Lakes Loon Survey; Loon Range Data 2022; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 6.2. Downloaded Dec. 6, 2022.

Diverse Indigenous cultures — from Inuit to Anishinabek — tell stories about loons as kin, highlighting their vision, perceptiveness and call. In contrast, early European settlers had their own reactions to the primordial call of the loon, reactions of violence and control. Henry David Thoreau described the sound of the loon as “the wildest sound.” “His usual note was this demoniac laughter, yet somewhat like that of a water-fowl,” he wrote in Walden. “But occasionally, when he had balked me most successfully and come up a long way off, he uttered a long-drawn unearthly howl, probably more like that of a wolf than any bird.” This association between loons and wolves motivated a great deal of the 19th-century perception of the bird. For hunters and fishermen, the loons’ status as predators marked them as competitors for resources. A recent article in Environmental History, titled “Loons and the Risk of Extinction in a Warming, Toxic World,” noted that “early conservationists targeted loons for eradication” just as they did with wolves, before the fundamental concept of ecological balance was widely accepted. “Indigenous perspectives on loons as kin, with special powers of vision and insight, have historically had less influence on loon wildlife management,” note the authors.

During the first week of life, loon chicks ride on their parents’ backs both to stay warm and to stay safe from predators.

At two or three weeks old, a loon chick sports light brown plumage. It can already dive and swim underwater for up to 15 meters.

At eight weeks, this loon is almost the size of an adult. It already forages for some of its food and will be able to fly in about a month.

That balance is now under threat. Birds Canada recently used 40 years of volunteer data from its Canadian Lakes Loon Survey to look at the “mysterious declines” in what it calls “loon productivity” — that is, the number of young that loons produce which survive beyond six weeks. They found the number of common loon chicks raised to independence has declined by 1.4 per cent per year since the survey began, and if these trends continue, it’s likely the overall population will start to fall. This echoes the results of a 27-year study out of northern Wisconsin that found common loon fledgling success declined by 26 per cent, with the overall adult population dropping by 22 per cent. One theory that explains these declines posits a combination of acidity and mercury in the lake water, plus climate warming. It’s likely that other factors, as yet to be uncovered, are also at play. Both surveys force us to confront the possibility of loonless lakes; they would be sadder, lonelier places.

After preening, a loon will flap its wings while shaking its head to lift itself as high out of the water as possible. This loon created a golden spray in the early morning light on Big Rideau Lake, Ont.

Loons are gregarious; they come up right beside the boat or the dock, sometimes curiously, sometimes indifferently, but never as a threat or as a victim. Loons aren’t afraid of us, and we’re not afraid of them. Perhaps that is why their call feels so companionable. Anyone who has been visited by a loon in the early morning mist on a lake has felt a fellowship of time and place. The loon has a life cycle familiar to the cottager it encounters, spending the winter surviving on the rough oceans of the wider world, then summering in the calm lakes of the enclosed interior. The change of location changes its eyes. Brown on the ocean turns red in the interior.

When they dip beneath the surface, loons blow air out of their lungs and flatten their feathers to expel air from their plumage, allowing them to dive quickly and swim fast. Under the surface, their hearts beat more slowly, allowing them to conserve oxygen.

Loons position fish to eat them head first so the dorsal fin lays flat when the fish is swallowed.

Loons have distinctly loonlike habits and ways of being. Simply put, they aren’t like other birds. They are even more foreign to us than other species. The loon has not evolved pneumatic bones, the hollow structures that make flying easier. A loon’s bones are heavy, allowing it to dive. In the world of lakes, it goes between landscapes. It is a creature of the air. It is an underwater creature. It nests in the reeds. It goes everywhere. Whenever we happen to encounter loons, usually in pairs, bobbing on the surface of the lake, they are at a crossroads, in between one environment and another. The loon’s eye sees from every perspective what we see from one.

An adult loon in the moments before it breaks the surface. It’s estimated that a pair of loons with two chicks can eat almost half a tonne of fish over 15 weeks.

The loon has a voice, but not a voice we recognize. That’s what makes it so human and so inhuman at the same time. The loon has a call, like a bugle call, a call to prayer. The sound is paradoxical, alien yet familiar.

It’s that paradoxical state that makes the call of the loon so unforgettable. That’s why it’s on the one dollar coin in Canada, as a symbol for the wilderness as a whole, a sound synonymous with remote solitude but also at-homeness with the landscape. The feeling the call of the loon evokes is a deep longing to be with nature as ourselves and not ourselves, to be human and wild at once. The indelibility of the call marks that longing which, in a part of us, never goes away.