Get outta ma swamp!

he Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) cover

Some good news for the watershed: The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) completed 93 projects that helped restore more than 4,000 acres of fish and wildlife habitat last year, according to a recent report published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. One such project was combatting the invasion of the red swamp crayfish.

Originally from the southeastern United States, the red swamp crayfish have become quite the globe trotter. They are commonly spread by unsuspecting pet owners releasing them into the wild. Now researchers in Michigan, funded by the GLRI, are leading the charge to develop a strategy to eradicate the invasive crayfish. “They’re just so prolific,” says biologist Kathleen Quebedeaux, in the report . “They make so many eggs and are extremely hardy. It seems like they can live anywhere.”

Red swamp crayfish are more aggressive than native crayfish, outcompeting them for food and space. They burrow underground and cause unwanted drainage from wetlands. If left unchecked, the impacts will ruin water quality and collapse riverbanks which can dry up beds of manoomin (Anishinaabemowin) or wild rice. “ People are paying attention because it’s not just Michigan; it’s the entire Great Lakes basin,” says Brian Roth, an associate professor at Michigan State University.

Roth said that this GLRI-funded project is different from any other he’s been a part of, stating that successful management of invasives requires extensive time to develop strategies and apply them. That’s something this funding supports. “It is our rapid integration,” said Roth. “I’m not talking 10 years here; I’m saying in the next year we’ll find a way to scale a lab project up to the field.” Efforts to control the crayfish so far have included daily trapping, x-ray sterilization, filling burrows and predation control.

The GLRI was created in 2010 by the Fish and Wildlife Service. Each year, the initiative is entrusted with more than U.S. $575 million through interagency agreements with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to amplify conservation efforts across the Great Lakes basins.

A glimmer of hope for communities struggling without clean drinking water

Steve Johnson, Unsplash

Access to clean, safe drinking water is a fundamental human right — and yet hundreds of First Nations across Canada have suffered without safe drinking water for years, leaving them exposed to illness, skin conditions and a general sense of despair. But there may yet be hope on the horizon.

In December 2021, after a two-year court battle, the First Nations Drinking Water Settlement was approved. The settlement will provide monetary compensation to First Nations communities who were subject to a drinking water advisory that lasted at least one year between Nov. 20, 1995 and Jun. 20, 2021. The deal covers 120 communities and 142,000 individuals from 258 First Nations, and the compensation claim period officially closed March 7.

The settlement was derived from national class action lawsuits against the Government of Canada in 2019, spearheaded by Neskantaga First Nation, Curve Lake First Nation, and Tataskweyak Cree Nation, with help from McCarthy Tétrault LLP. The lawsuits addressed drinking water advisories in First Nations and Canada’s failures to take reasonable steps to ensure First Nations communities have access to clean drinking water.

The settlement will not only compensate those affected by the lack of clean water, but also fund the “construction, operation and maintenance of infrastructure” designed to provide First Nations and Individual Class Members—members of the groups on whose behalf the lawsuit was filed—with regular access to drinking water in their homes.

Oneida Nation of the Thames, a community south of London, Ont., has been under a boil water advisory since 2019, which became an apparently permanent state of affairs in September 2020. The advisory means the community’s water supply is unsafe to drink without boiling it, and special precautions apply for the use of untreated tap water.

Members of the Oneida Nation rushed to fill out application forms as the claim deadline approached, and, in March 2023, the Oneida Nation received $43 million from Indigenous Services Canada to connect the existing Oneida water supply system to the Lake Huron primary water supply System. The project will provide clean drinking water to the community — that’s approximately 528 homes and all existing residential buildings. The ongoing water infrastructure project is estimated to take 18 to 24 months to complete.

After years of fighting for their voices to be heard, the settlement and federal funding is somewhat of an acknowledgement that the government is listening. Hopefully, they will continue to work harder to help those who have struggled for far too long.

NOAA receives major funding for future water level forecasting research

The Department of Commerce and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced a $3.72 million fund for supporting Great Lakes water level forecasting.

Water level forecasts for the Great Lakes are crucial for commerce, recreation and safety throughout the region, both in Canada and the United States. Adequate water levels based on regional needs is necessary to maintain the Great Lakes’ economic hub, supporting jobs in tourism, recreation and marine transportation.

Currently, water level forecasts can predict the Great Lakes water levels six months in advance. This project is designed to extend and improve seasonal forecasts to one year in advance using technologies such as machine learning.

Machine learning is a form of artificial intelligence that uses algorithms to learn data and make predictions and forecasts for future events. It has a variety of environmental uses including forecasting air quality, simulating changing climate patterns, and forecasting water levels. NOAA uses hydrographs to see seasonal and decadal changes in the flow and discharge of the Great Lakes waterways. With machine learning, that data could be used to make predictions and forecasts farther into the future than the current six-month prediction rate.

The new advanced forecast will not only give communities more time to prepare for potential hazards, such as flooding, but it will also enable researchers at NOAA to analyze in more detail how global and regional climate patterns affect the Great Lakes.

“Having a more accurate, long- term advanced forecast will help communities plan and manage for changes in lake levels to reduce impacts and protect their citizens from flooding,” Debbie Lee, NOAA’s Great Lakes Environment Research Laboratory director, said in a NOAA news release.

Enhancing water level forecasts will boost confidence in predicting water level fluctuations and also highlight critical data for decision-makers, bolstering initiatives aimed at fortifying coastal resilience.

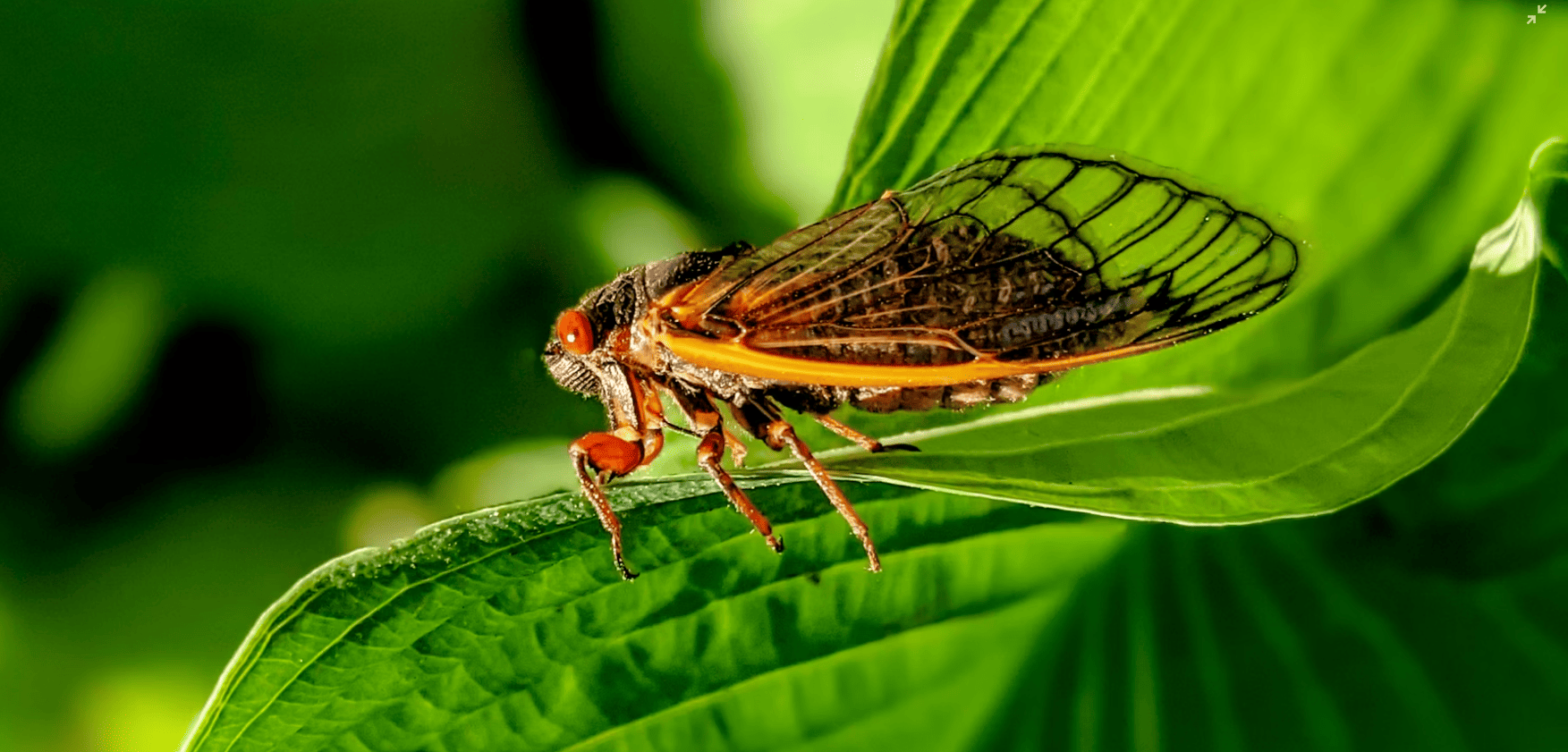

A symphony of a trillion cicadas

Cicada, Bill Nino (Unsplash)

2024 is set to be a noisy and active year for cicada populations in North America.

The continent is home to four species of cicada, one of which emerges every 13 years, while the rest emerge on a 17 year cycle. However, in 2024, the emergence of these species is set to synchronize — resulting in the co-occurrence of more than one trillion cicadas in a single season.

It’s a co-occurrence that hasn’t been seen since 1803 — and won’t be seen again in our lifetimes (unless, that is, you happen to live another 221 years!).

This influx of cicadas — typically only lasting a few weeks — can have drastic impacts on the environment. Cicadas can provide food sources for birds and other wildlife, and when the emergence is over, they decay and contribute nutrients to the forest ecosystem. “It will lead to some decaying insects and some issues around that. But it’s a very brief thing. That, ultimately, is part of how ecosystems function normally,” Alan Carroll, a professor in the Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences at the University of British Columbia, told The Weather Network.

This uncommon occurrence also provides the opportunities for researchers to promote community science initiatives, such as asking the public to log their observations on the Cicada Safari app to document the occurrence of cicadas across a wide geographic range.