A cardinal warms his legs by tucking them under his fluffy body. Photo by Meganzopf (Pixabay: Link)

Obviously, birds are covered in fluffy feathers to keep their little bodies warm. We know this. In fact, we covet their warmth and use their down feathers in our own winter jackets and duvets.

But have you seen their feet? How is it that those spindly little legs don’t get frostbite and fall right off when the temperatures plummet? You might see the little chickadee sitting out in the snow and wonder “why on earth didn’t you just migrate south?”

A chickadee endures the snow. Photo by Meganzopf (Pixabay: Link)

It turns out that our feathery friends have a pretty fascinating mechanism that keeps their legs warm in winter. Let’s dig right in…

First, the basics: cold bird behaviour

There are some behaviours that birds do to help keep their legs warm. You have probably noticed birds sitting on branches with their little legs tucked under their feathers. They bring their legs closer to their bodies for warmth, like us tucking our frozen fingertips into our armpits.

Many bird species will huddle together for warmth, like the famous emperor penguins. Other species do this too, like little bluebirds and big geese. Birds can also shiver their flight muscles to help generate heat. But this can be tiring, so they don’t do it very often.

Canada geese huddle together to conserve their heat. Photo by skeeze (Pixabay)

Some birds, like many cold weather-enduring mammals, will gorge themselves before the winter months to produce extra fat. This body fat will act as a protective layer against the cold and as extra energy storage.

Now for the super cool stuff: bird feet physiology

Bird legs are built to regulate temperature. Most birds have legs and feet that are covered in rough, scaly skin. Like a leather jacket, this layer will help to limit heat loss.

This blue jay doesn’t seem to mind having legs buried in snow. Photo by NatureLady (Pixabay: Link)

Bird legs are also very small, compared to their body size; like fat puffballs sitting on little twigs. These spindly legs have a very low surface area, meaning that there is only a small amount of skin that is exposed to the cold.

But what about inside their legs?

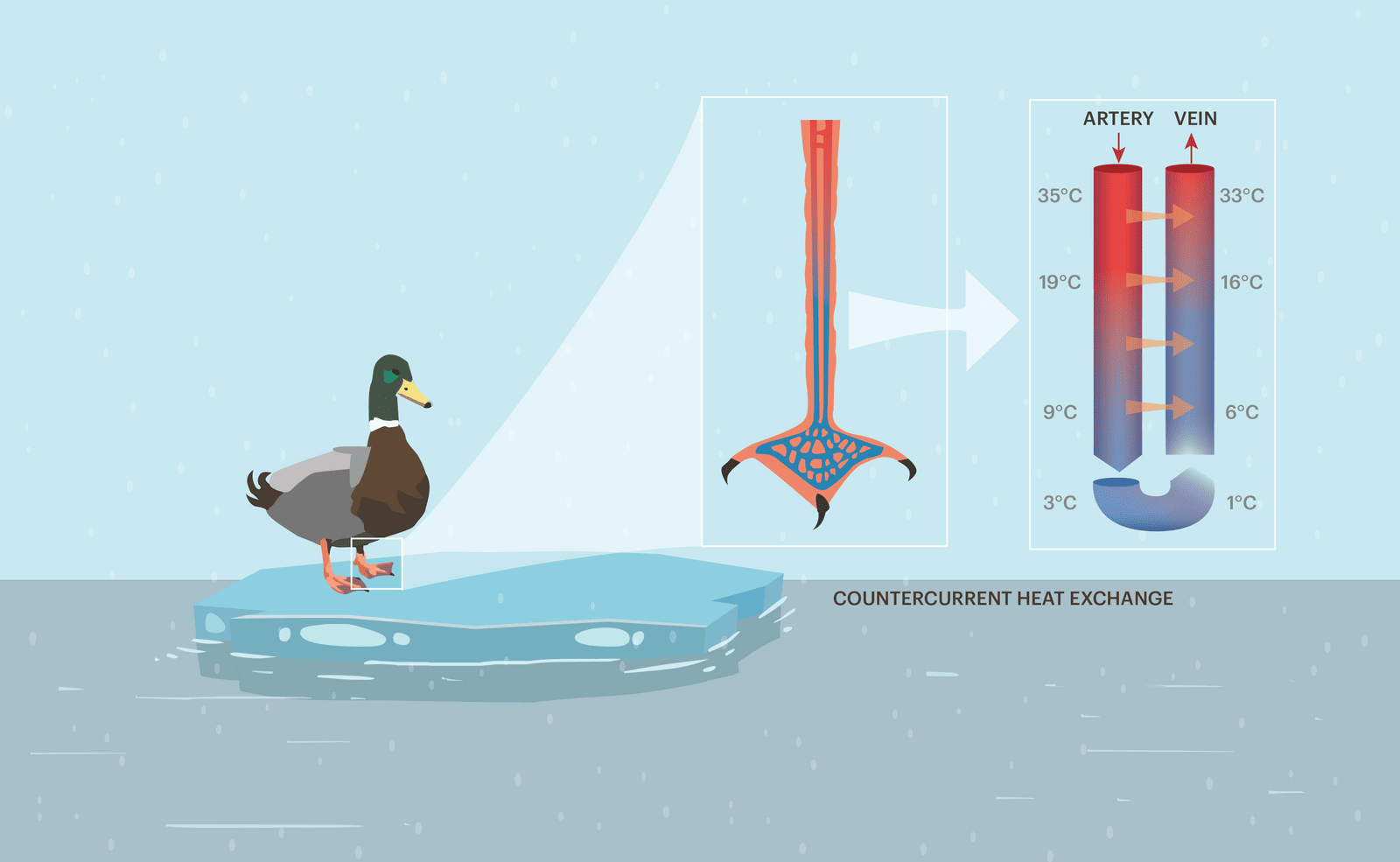

Birds use a countercurrent exchange system of blood in their legs. Countercurrent exchange simply means that fluids (liquids or gases) within the body pass in opposite directions, exchanging or transferring properties. These properties could be heat, nutrients, fluids, or oxygen (like fish gills).

In bird feet, veins and arteries are arranged so that heat can easily be transferred between the two, keeping their feet warm. Warm blood from the body is pumped down towards the feet, while cold blood is pumped up from their feet toward the body.

Heat from the warm arterial blood transfers by conductance into the veins, helping the bird maintain their body temperature. Graphic by Meghan Callon

Birds have a lace-like network of capillaries (small blood vessels) that create a larger surface area for this heat to be easily exchanged. Lower temperatures can be maintained in the feet and controlled, so that they don’t waste energy losing a lot of heat to their cold surroundings. In the same way, birds could use this system to help cool down if they get too hot.

If birds did not have this setup, the blood pumping straight to their feet would get cold quickly. They would have to use so much extra energy to warm up blood once it reached their core.

Countercurrent heat exchange helps these mallards keep warm as they march through the icy water. Photo by garten-gg (Pixabay: Link)

This impressive system is especially important in resident aquatic birds, like mallard ducks and Canada geese. This exchange system helps to prevent the birds from losing too much heat to the surrounding water.

So, there you have it! The next time you see a duck standing on a frozen pond, don’t fret. You don’t need to start knitting duck slippers anytime soon. Those quackers are very well adapted to our frigid winters.